Than Hussein Clark

Despair5 & 7 rue de Beaune, Paris

During our interview to prepare this text, Than tried to retrace the conception of an exhibition that had been postponed many times. His project, interrupted by personal or collective tragedies, has had different versions, some of which have been put aside as his explorations have progressed, or else put off for later. Borne up by an inhabited, chaotic stream of words, he waltzes me along the traces of more-or-less well-known characters from the first half of the 20th century: Pierre-Lucien Martin, a Parisian maker of art books during World War II (he is supposed to have had in his possession the first manuscript of Genet’s The Maids), Philip R. Perkins, an American painter who frequented the gay New-York demi-monde of the 1940s and was a friend of the founders of the magazine View (Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler), or else Charles de Beistegui, the ostentatious Franco-Mexican heir, decorator and art collector, who was behind the scandalous Bal du siècle of 1951 at the Palazzo Labia in Venice, which he owned. Then came the A-listers : Marcel Duchamp, Greta Garbo, Marcel Broodthaers or else Joseph Beuys. Lost in the complexity of a layered conversation, I suddenly realised that I’d been absorbed into a demonstration of “queer gossip”: that historic-speculative practice that brings in rumours or gossip to make good the gaps in history and its uncertainties. As a confirmed collector of memorabilia and minority narratives, Than Hussein Clark explores the historic density of queer lives in the 20th century: he seeks out traces and digs up personal stories, wondering how some individual trajectories may, or may not, have coincided.

For Despair, he has taken an interest in the filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder and his 1978 film of the same name, adapted from Vladimir Nabokov’s novel. In it, Dirk Bogarde plays the owner of a chocolate factory, Hermann Hermann, who organises his disappearance after meeting his doppelgänger. And yet, what runs through this exhibition is the withdrawal from public life of Greta Garbo, the Swedish-American star of the silent screen. In one of the six cabinets presented by the artist, a checkerboard is occupied by a variation on Joseph Beuys’s famous declaration: “the silence of Duchamp is overrated”(1). Taken from a 1964 action that criticised the artist’s decision to abandon art and devote himself to writing and chess, it has here been adapted to the silence of Greta Garbo, to which no one would attach the same intellectual importance. It is a point of departure so as to think about questions of disappearance, absence, and a productive negativity.

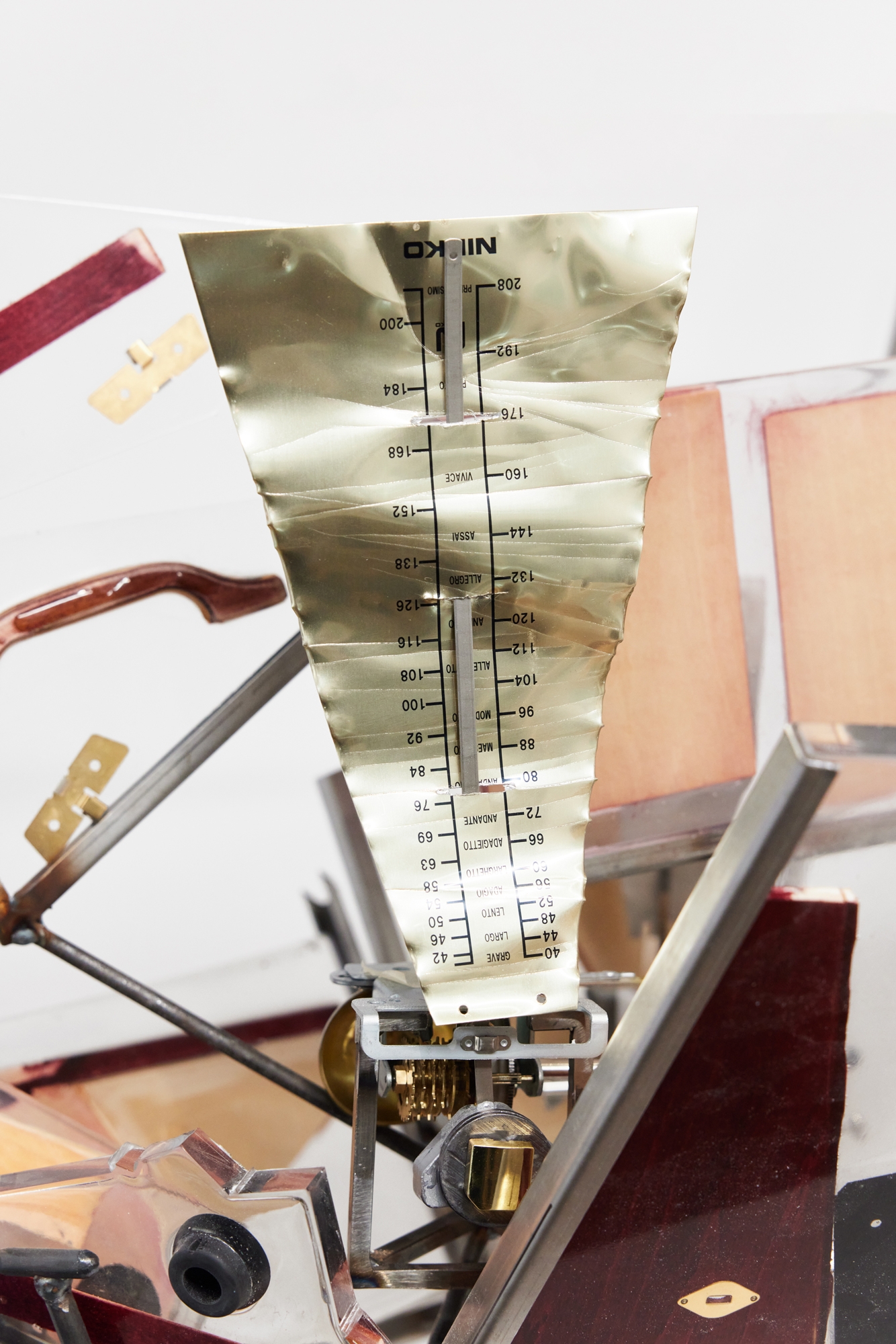

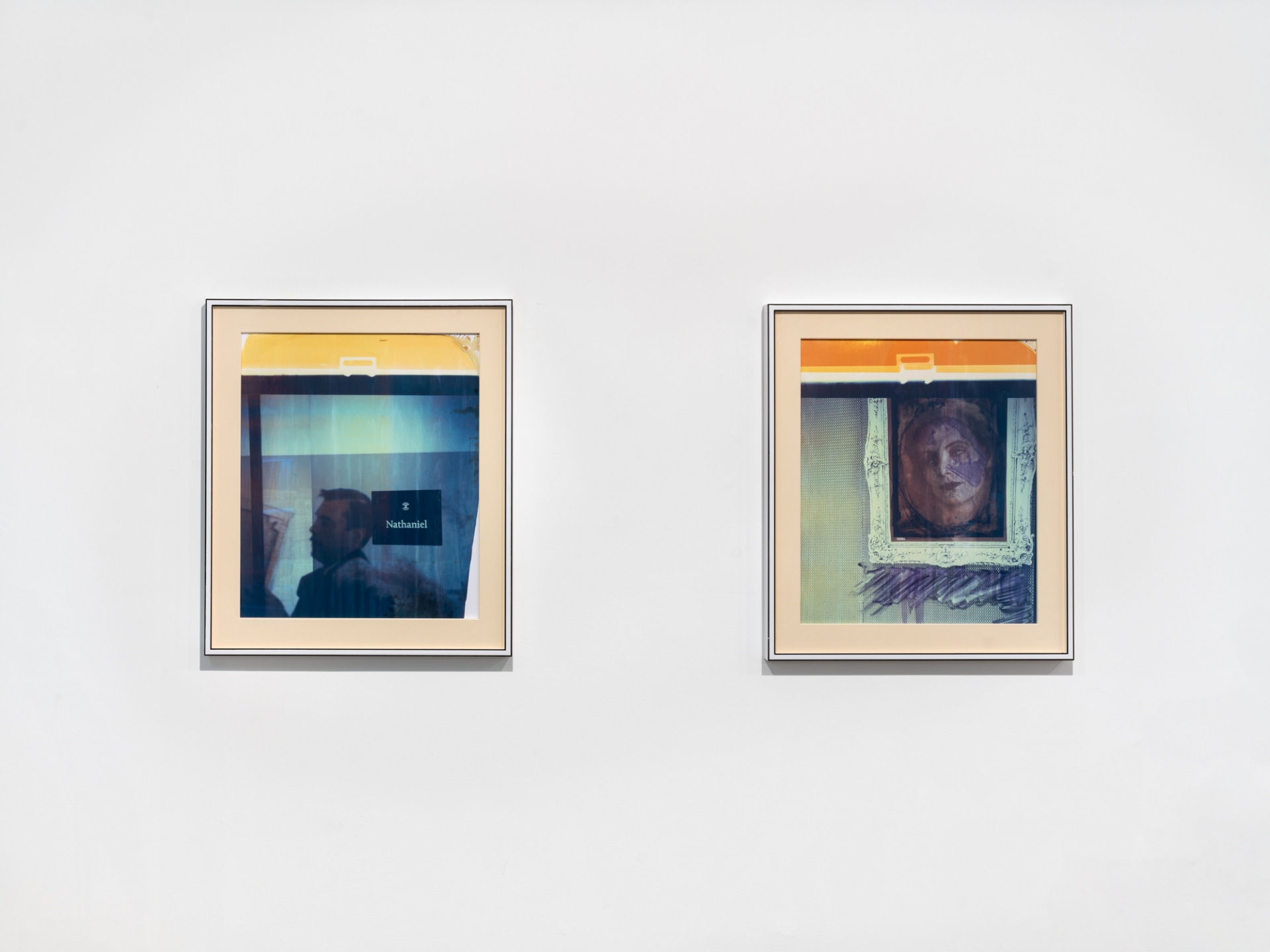

The exhibition is inhabited by photo montages that provide Greta Garbo and Dirk Bogarde with a space to meet each other, on the basis of Polaroids stolen from the Rothschild Bank in London and objects consecrated by Duchamp. We also encounter photographs of the body of the artist’s father, dressed up as Captain Hook, made shortly after his passing. The character of Peter Pan, haunted by a crocodile and a clock, here can be seen as a figure of human finitude. Each of the cabinets presented by the artist is marked by the influence of the architect and interior designer Emilio Terry, and contains a ready-made : a boat made from metronomes, an architectural model of Broodthaers’s famous white room, an original drawing by Philip R. Perkins, or else a painting that belonged to the artist’s father.

In line with a conceptual art to which he had previously paid little attention (too straight), Than Hussein Clark considers the question of a queer ready-made that would be more attentive to its provenance than its function as an object. We might wonder about the gossiping power of objects that convey queer stories: how do they allow us to trace out lineages, or produce embodiments of lives that have preceded us ? In his book “Between You and Me” (2005), the historian Gavin Butt looks at gossip as a queer relational methodology: an action that maintains the process of heritage in an artistic community while deconsecrating the archive as a fixed and stable historical material. In this exhibition, a concern about producing connections while maintaining the irrational power of artworks is central: hence the artist’s love for the irreverence and anachronism of collages. There can also be seen his interest in affective design, haunted by the spectre of functionalism. Behind the doors of the cabinets, skeleton-maids seem to dance or twitch, and the memory of Jean Genet is never far away.

(1) “Das Schweigen von Marcel Duchamp wird überbewertet.”

Lors de notre entretien pour préparer ce texte, Than tente de retracer la conception d’une exposition maintes fois reportée. Interrompu par des tragédies personnelles ou collectives, son projet a connu différentes versions, certaines délaissées au gré de ses recherches ou remises à plus tard. Porté par une logorrhée habitée et chaotique, il me fait zigzaguer sur les traces de personnages plus ou moins connus de la première moitié du XXe siècle : Pierre-Lucien Martin, relieur d’art parisien durant la seconde guerre mondiale (il aurait eu entre les mains le premier manuscrit des Bonnes de Genet), Philip R. Perkins, peintre américain orbitant autour du demi-monde pédé New Yorkais des années 40 et ami des fondateurs du magazine View (Charles Henri Ford et Parker Tyler), ou encore Charles de Beistegui, fastueux héritier franco-mexicain, décorateur et collectionneur d’art, à l’origine du sulfureux “Bal du siècle” tenu en 1951 au Palais Labia à Venise, dont il fut le propriétaire. Puis viennent les A-listers : Marcel Duchamp, Greta Garbo, Marcel Broodthaers ou encore Joseph Beuys. Perdu dans la complexité d’une conversation à tiroirs, je réalise soudain que j’assiste, absorbé, à une démonstration de queer gossip : cette pratique historio-spéculative qui mobilise la rumeur ou le commérage pour embrasser les manques et les incertitudes de l’histoire. En collectionneur assidu de memorabilia et de récits minoritaires, Than Hussein Clark explore l’épaisseur historique des vies queers du XXe siècle : il en cherche les traces et en exhume les histoires intimes, se demandant comment certaines trajectoires individuelles auraient pu, ou non, se croiser.

Pour Despair, il s’intéresse au cinéaste Rainer Werner Fassbinder et à son film éponyme de 1978, adapté d’un roman de Vladimir Nabokov. Dirk Bogarde y joue le propriétaire d’une usine de chocolats, Hermann Hermann, qui orchestre sa disparition après avoir rencontré son doppelgänger. Pour autant, c’est le retrait de la vie publique de Greta Garbo, actrice suédo-américaine et star du cinéma muet, qui traverse cette exposition. Dans l’un des six cabinets que l’artiste présente, un damier est investi par une variation de la célèbre phrase de Joseph Beuys, “le silence de Duchamp est surestimé”(1). Tirée d’une action de 1964 qui critiquait la décision de l’artiste de quitter l’art pour se consacrer à l’écriture et aux échecs, elle s’adapte ici au silence de Greta Garbo, auquel personne ne prêta la même portée intellectuelle. C’est un point de départ pour réfléchir à la question de la disparition, du manque, et d’une négativité productive.

L’exposition est habitée de montages photographiques qui offrent à Greta Garbo et Dirk Bogarde un espace pour se rencontrer, sur fond de clichés polaroïds volés dans la Rothschild bank de Londres et d’objets consacrés par Duchamp. On y croise également des photographies du corps du père de l’artiste affublé d’un costume du Capitaine Crochet, réalisées peu après son décès. Le personnage de Peter Pan, hanté par un crocodile et une horloge, campe ici une figure de la finitude humaine. Chacun des cabinets présentés par l’artiste est marqué par l’influence de l’architecte et décorateur d’intérieur Emilio Terry, et enclot un ready-made : un bateau réalisé à partir de métronomes, un modèle architectural de la fameuse salle blanche de Broodthaers, un dessin originel de Philip R. Perkins, ou encore un tableau ayant appartenu au père de l’artiste.

Sur le fil de l’héritage d’un art conceptuel auquel il n’a jusqu’ici prêté que peu d’attention (trop hétéro), Than Hussein Clark considère la question d’un ready-made queer qui s’intéresserait à la provenance plutôt qu’à la fonction d’un objet. On pourrait se demander quelle est la force de commérage des objets qui véhiculent les histoires queers : comment nous permettent-ils de tracer des lignées, de produire des incarnations des vies qui nous ont précédées ? Dans son ouvrage “Between You and Me” (2005), l’historien Gavin Butt s’intéresse au ragot comme méthodologie relationnelle queer : une action qui maintient le processus de filiation d’une communauté artistique tout en déconsacrant l’archive comme matériau historique fixe et stable. Dans cette exposition, le souci de produire des appartenances tout en maintenant une puissance d’irrationalité des œuvres d’art est central : d’où l’amour de l’artiste pour l’irrévérence et l’anachronisme du collage. On retrouve également son intérêt pour un design affectif, hanté par le spectre du fonctionnalisme. Derrière les portes des cabinets, des squelettes-soubrettes semblent danser ou s’agiter, et le souvenir de Jean Genet n’est jamais loin.

Text by Thomas Conchou, December 2024

Translated by Ian Monk

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

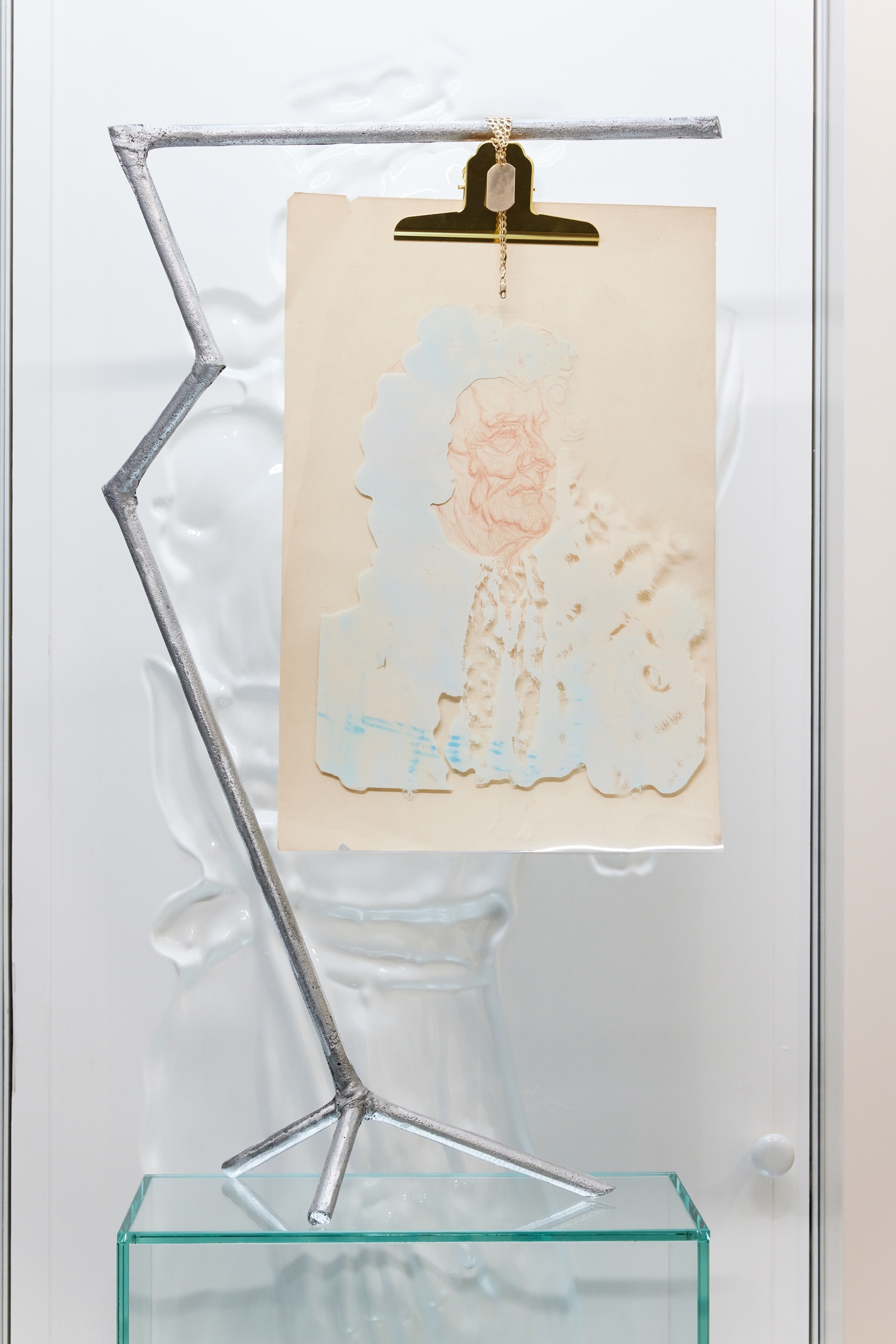

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Time as a Wig Overlaid), 2024

Steel, Enamel, Boiserie, Vacuum Formed Plastic, Glass, Cast Aluminium, Philip R. Perkins Life Sketch (1952), Screen Printed Acetate, Brass, Artists Gold Chain with Dog Tag, 222 × 109 × 65,5 cm

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Time as a Wig Overlaid), 2024

Detail

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Flat Time), 2024

Steel, Enamel, Boiserie, Vacuum Formed Plastic, Glass, 18th Century French Hour Glass, 19th Century Italian Marble Marquetry Card Box, 222 × 109 × 65,5 cm

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

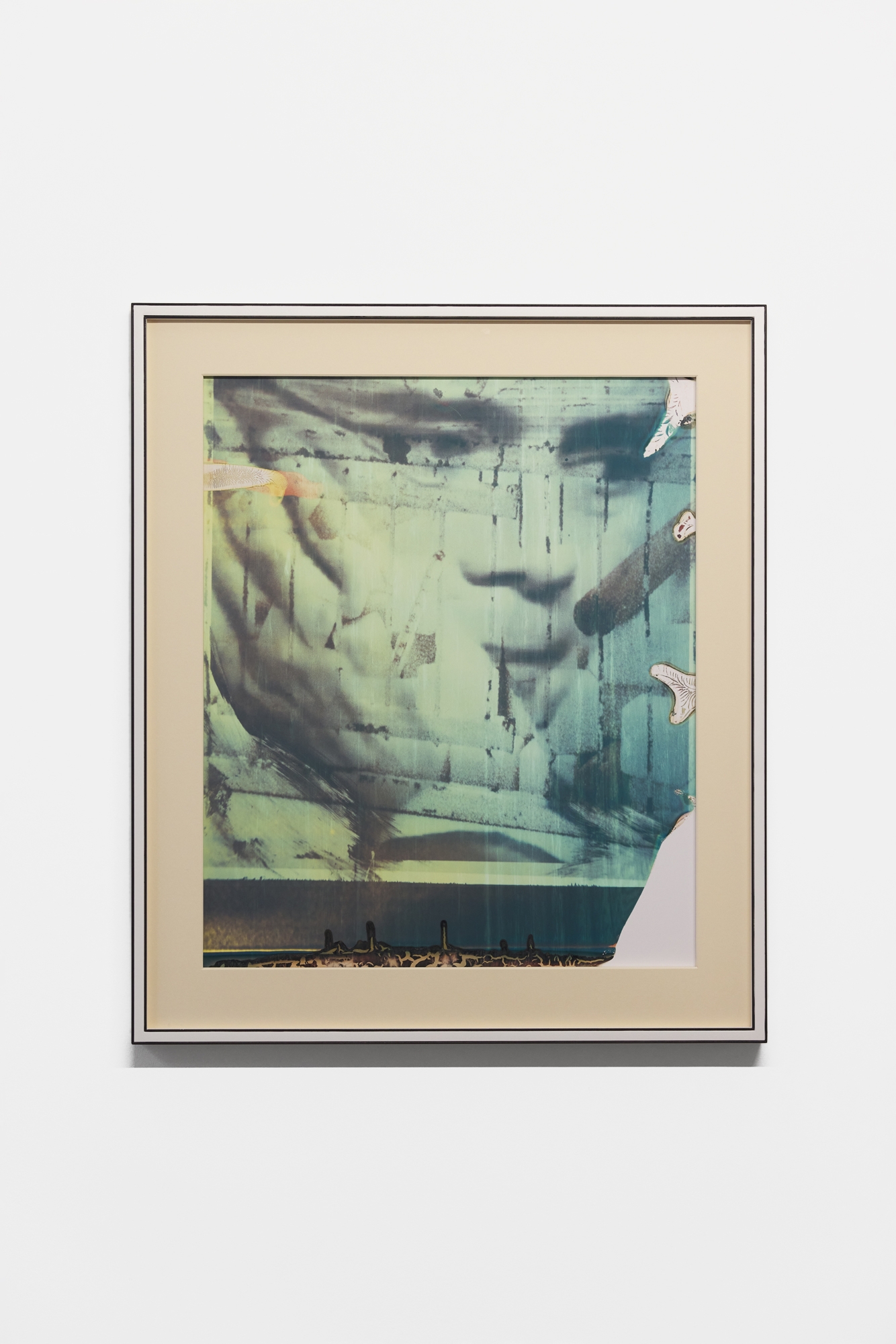

Than Hussein Clark, Lobby Cars for A Viennese Compression (Fidelity), 2024

Polaroid 24inch Dead Stock, 59 × 50 cm (framed: 74,5 × 64 cm)

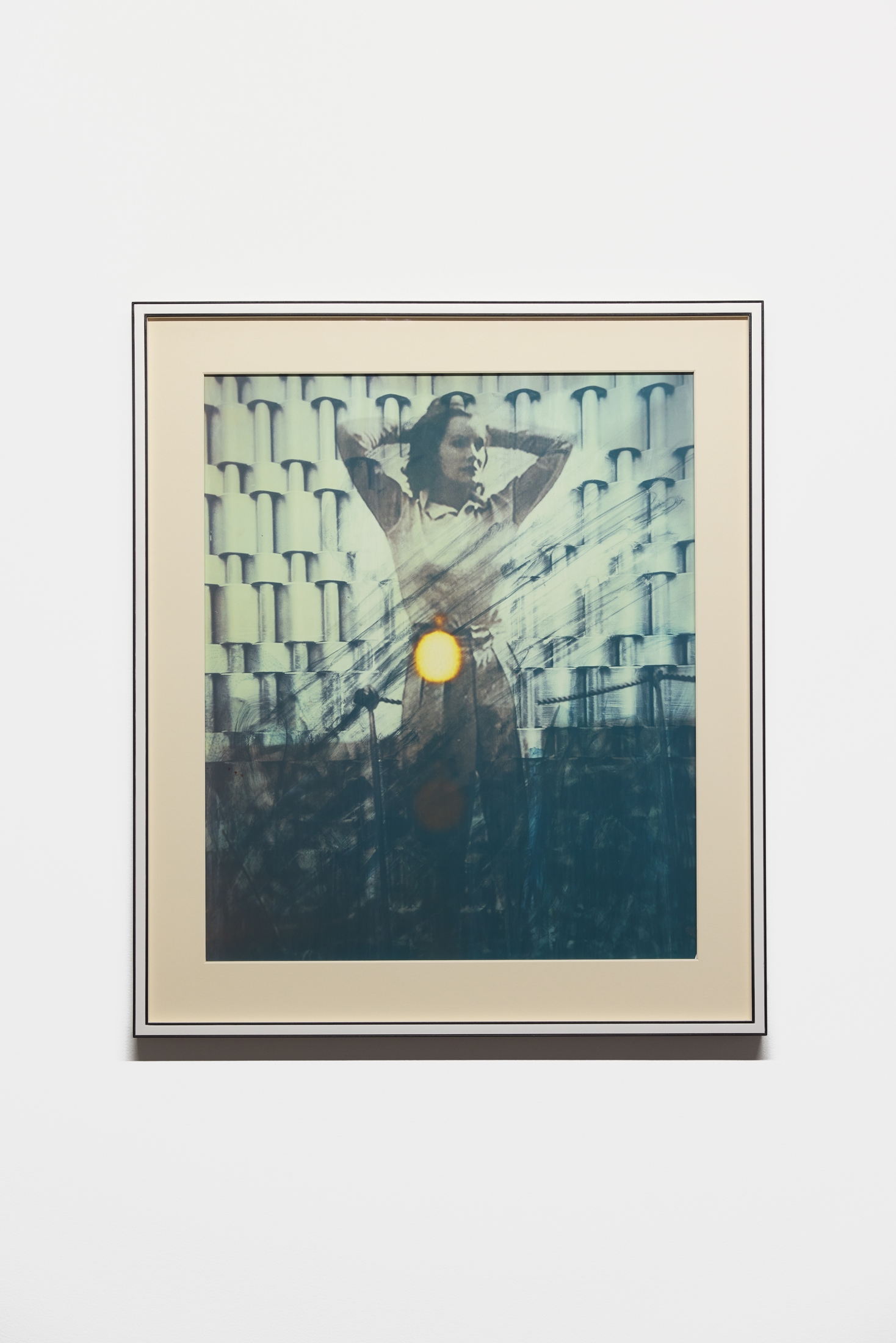

Than Hussein Clark, Lobby Card for A Viennese Compression (Thrift), 2024

Polaroid 24inch Dead Stock, 59 × 50 cm (framed: 74,5 × 64 cm)

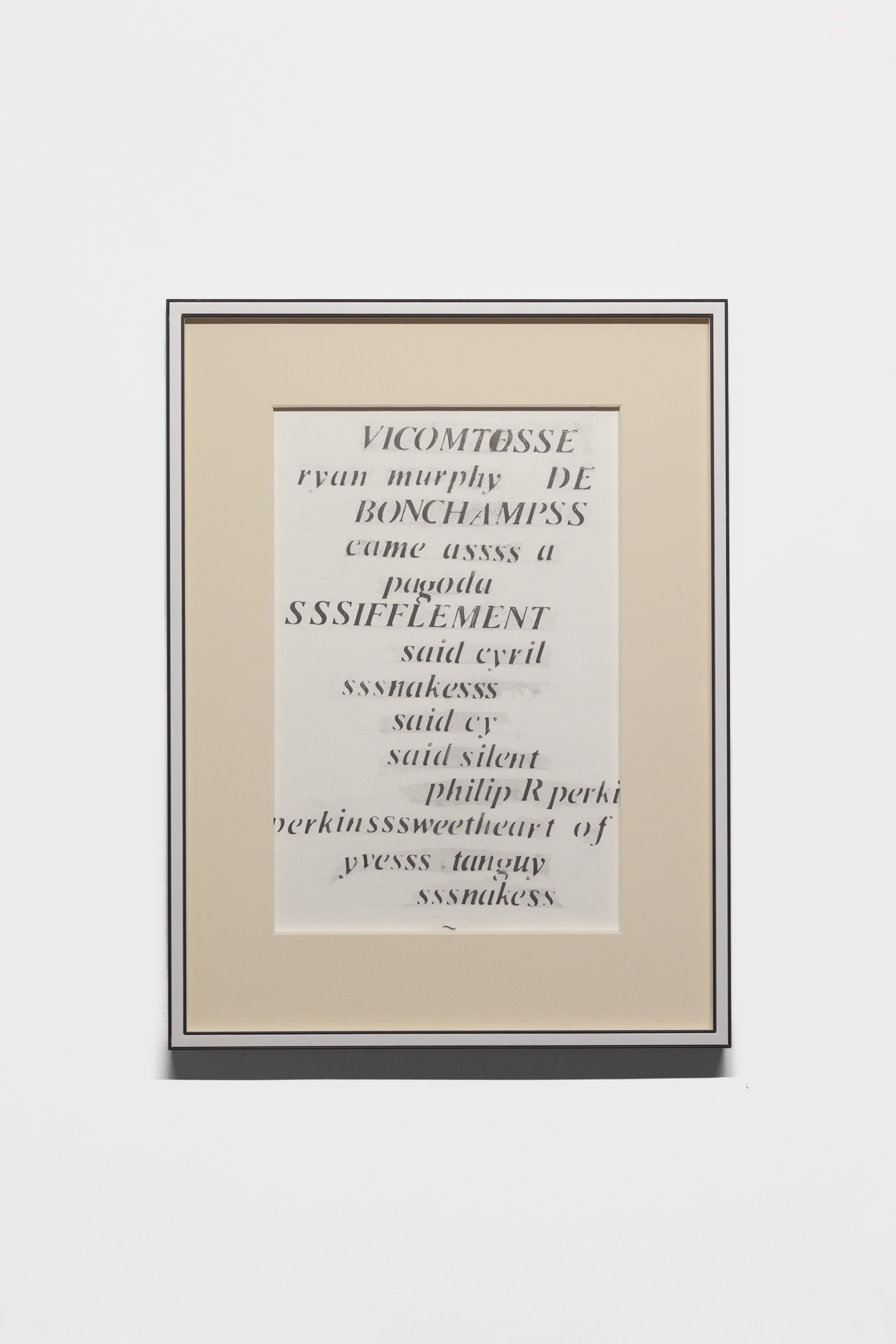

Than Hussein Clark, Ryan Murphy Invitation/Incantation (Sifflement), 2024

Graphite on Saunders Waterford, 44 × 29 cm (framed: 63,5 × 48 cm)

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Mr. Rabin or The Voyage to Shanghai, 2024

Resin, Steal, Japanese Condoctors Metronomes, 70 × 41 × 51 cm

Than Hussein Clark, Mr. Rabin or The Voyage to Shanghai, 2024

Detail

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Lobby Card for A Viennese Compression (Interests), 2024

Polaroid 24inch Dead Stock, 59 × 50 cm (framed: 74,5 × 64 cm)

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey, (The Style of Time), 2024

Steel, enamel, boiserie, vacuum formed plastic, glass, polar landscape by Operti, letraset print, brass, arcylic, 222 × 109 × 65,5 cm

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

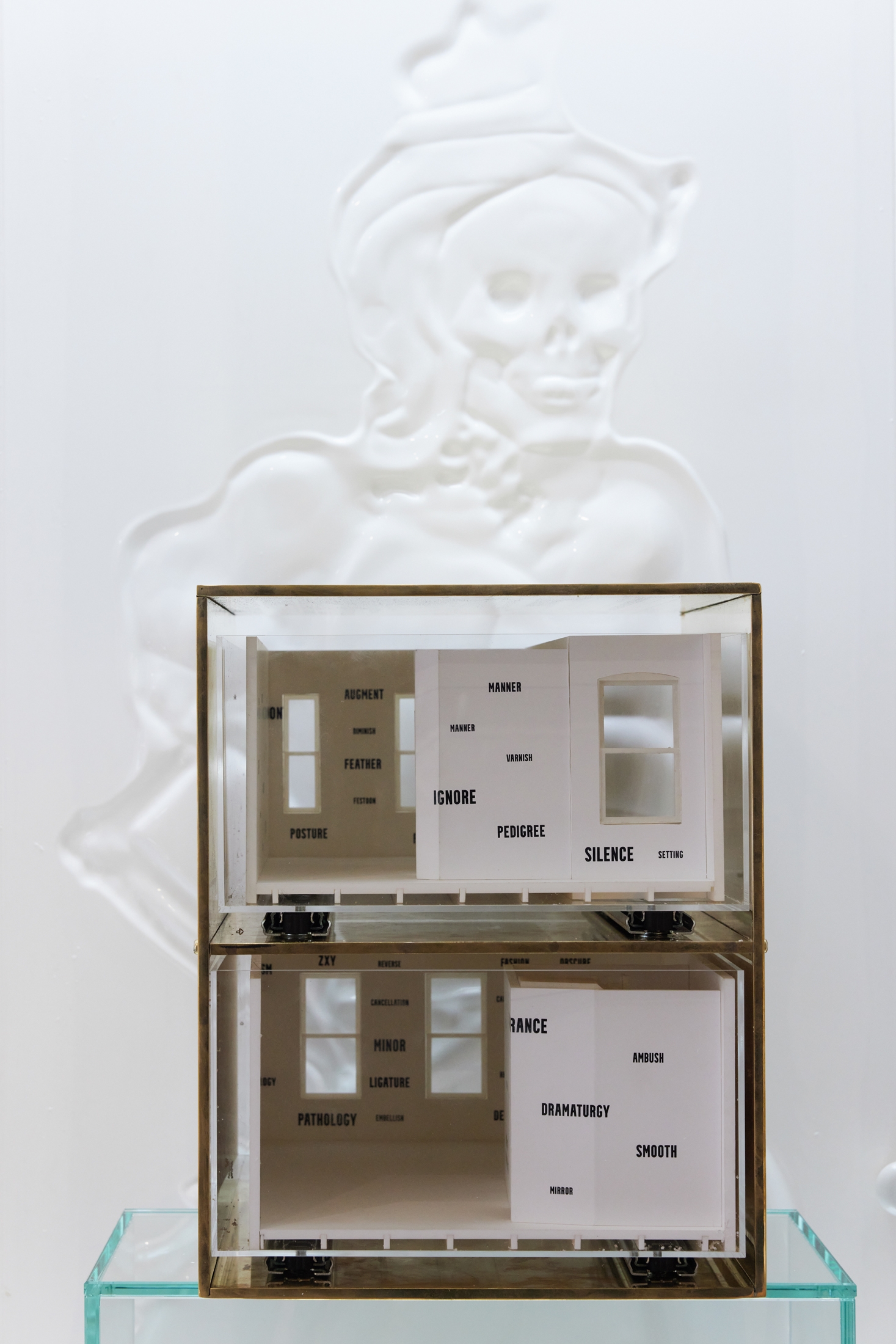

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Time in a White Room After Marcel Broodthaers), 2024

Steel, enamel, boiserie, vacuum formed plastic, glass, brass, arcylic, 3D printed architectural model of Apartment 2, 103 Mosco Street, NY, wallpaper, 222 × 109 × 65,5 cm

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Time in a White Room After Marcel Broodthaers), 2024

Detail

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Entrée Gauche (After Emilio Terry), 2024

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Time in Nashville), 2024

Steel, enamel, boiserie, vacuum formed plastic, gauche, brass, copy of Yves Tanguy by Andre Breton (Book Design by Marcel Duchamp), 222 × 109 × 65,5 cm

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey (Time in Nashville), 2024

Detail

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Nautical Portrait Cancellation - Ahab in Artic Fever (Madame Plum Charade), 2024

Silver Gelatin Print, Duchamp Retrospective Posters, Cracked Gesso, Pigment, Patinated Brass, 69 × 62,5 × 210 cm

Than Hussein Clark, Nautical Portrait Cancellation - Ahab in Artic Fever (Madame Plum Charade), 2024

Detail

Than Hussein Clark, Nautical Portrait Cancellation - Ahab in Artic Fever (Madame Plum Charade), 2024

Detail

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey, (Time to Disapear), 2024

Steel, enamel, boiserie, vacuum formed plastic, polished aluminium, pins, venner, Stainless Steal, Greta Garbo Fan Cards, 222 × 109 × 65,5 cm

Than Hussein Clark, Vitrine, 11 Rue Larrey, (Time to Disapear), 2024

Detail

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, Lobby Card for A Viennese Compression (Hole in the Head), 2024

Polaroid 24inch Dead Stock, 59 × 50 cm (framed: 74,5 × 64 cm)

Than Hussein Clark, Lobby Card for A Viennese Compression (The Idle Yankee), 2024

Polaroid 24inch Dead Stock, 59 × 50 cm (framed: 74,5 × 64 cm)

Exhibition view, Than Hussein Clark, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, Despair, 2024, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Than Hussein Clark, At the Symposium, 2024

Patinated Brass, 53 × 17 × 75 cm

Work views: Alex Kostromin

Exhibition views: Martin Argyroglo

Image courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur

PARIS — Cascades

9 rue des Cascades

75 020 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

PARIS — Beaune

5 & 7 rue de Beaune

75 007 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

Contact

PARIS — CASCADES: +33 (0)9 54 57 31 26

PARIS — BEAUNE: +33 (0)9 62 64 38 84

info@galeriecrevecoeur.com