Ladji Diaby, Inès Di Folco Jemni, Tomasz Kowalski, Cezary Poniatowski, Peng Zuqiang

it was a hot day, a day that was blue all through5 & 7 rue de Beaune, Paris

“It was a hot day, a day that was blue all through,” we can read in the opening paragraphs of Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading, written in 1932. According to the author, it is his most poetic novel. A dystopic tale in which the main character — a prisoner waiting for his sentence to be carried out — invents an imaginary world made up of metaphors and allusions. In which a day can become blue, a jailer can waltz and a spider can talk. The novel’s controversial end suggests that the prisoner escapes from being executed thanks to his imagination, which transports him on a journey between time and space. Azar Nafisi analysed this book in her autobiographical novel, Reading Lolita in Tehran (2002). While teaching western literature at the University of Tehran during the 1979 revolution, she extolled the strength of fiction and its transcendent power. She wrote how, under a regime that annihilates metaphors and allusions, the understanding of stories and of literature withers away. Fiction becomes flat and banal in the service of a cause and the nuances of narrative disappear.

Daring to lay down an image, to hold reality at a distance, to liberate yourself from it or deny it are all ways that artists have created in order to be free. Fiction persists in artworks despite the chaotic confusion of new data, and despite a perpetual and monotonous din. Stories, metaphors and imaginary tales lie at the heart of this exhibition.

Intergalactic worlds, drawing their references from all kinds of cultures, feature in Inès di Folco Jemni’s canvases. In her oil paintings, highlighted with Venetian turpentine and glitter, imaginary characters appear, with female traits, travelling in a fictional, indeterminate space. Details of towns with medieval architectures, magical, sometimes-carnivorous flowers, fairies, and dense, mauve sunsets can be glimpsed. The atmosphere of a sacred rite proliferates, wavering between Message, Souvenir and Médina.

In his sculptures, Ladji Diaby creates a new, highly personal language, linked to his home environment, in a direct relationship with his origins. There is always a question of objects and images, which he uses as transfers — a technique he exploits in his work to speak of spirituality, emotions, feelings and idols, but also of the absurdity of official, imposed narratives.

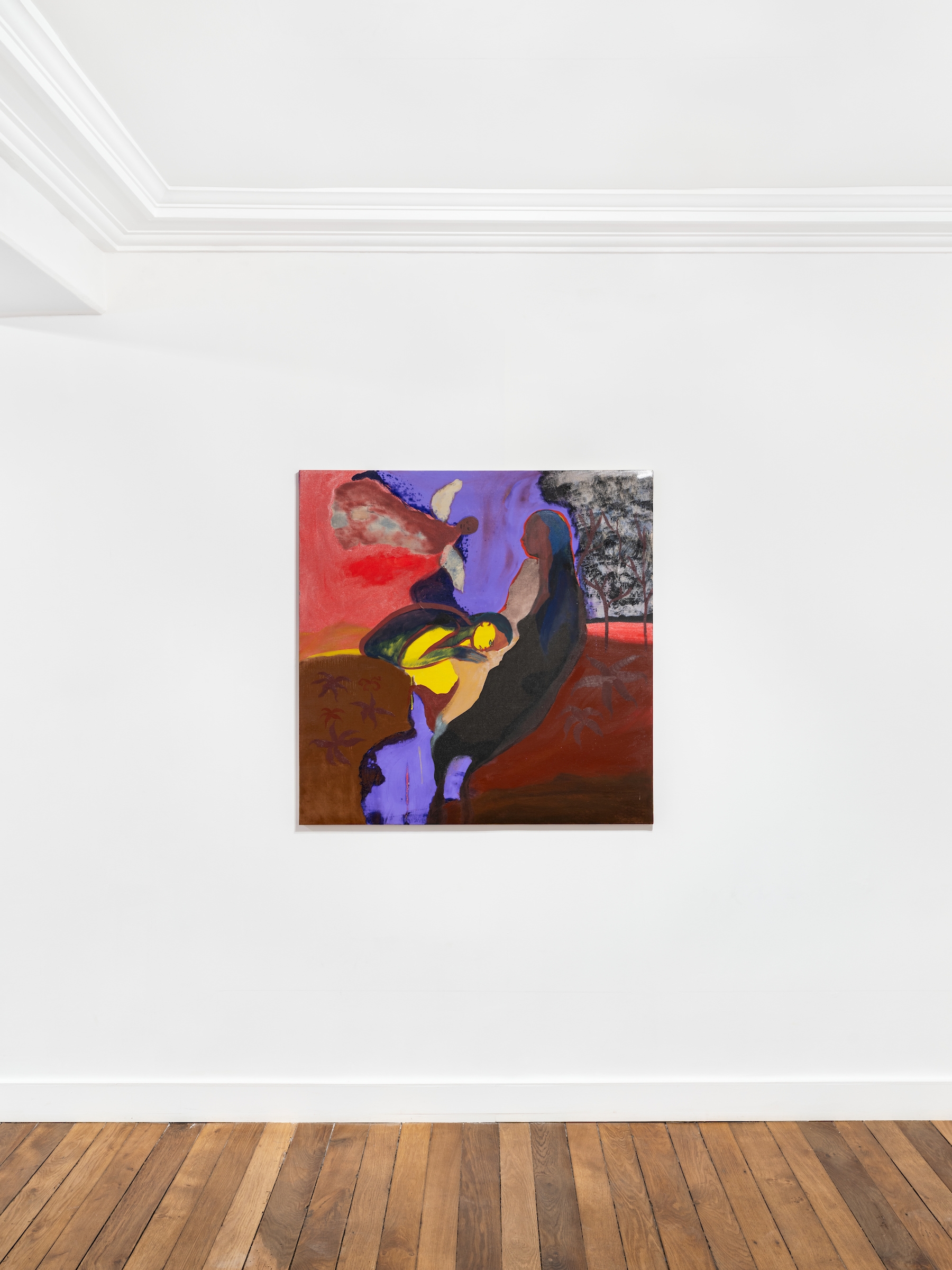

Tomasz Kowalski’s work oscillates freely between different eras and styles in the history of art, while producing an iconography in which his own, fragmented imagination can evolve. He destroys the hierarchy between sleep, dreaming and wakefulness while celebrating the freedom of the subconscious. His characters sometimes seem to vanish into depths of colour. In collaboration with his mother, the textile artist Alicja Kowalska, Tomasz Kowalski has also developed a tapestry practice.

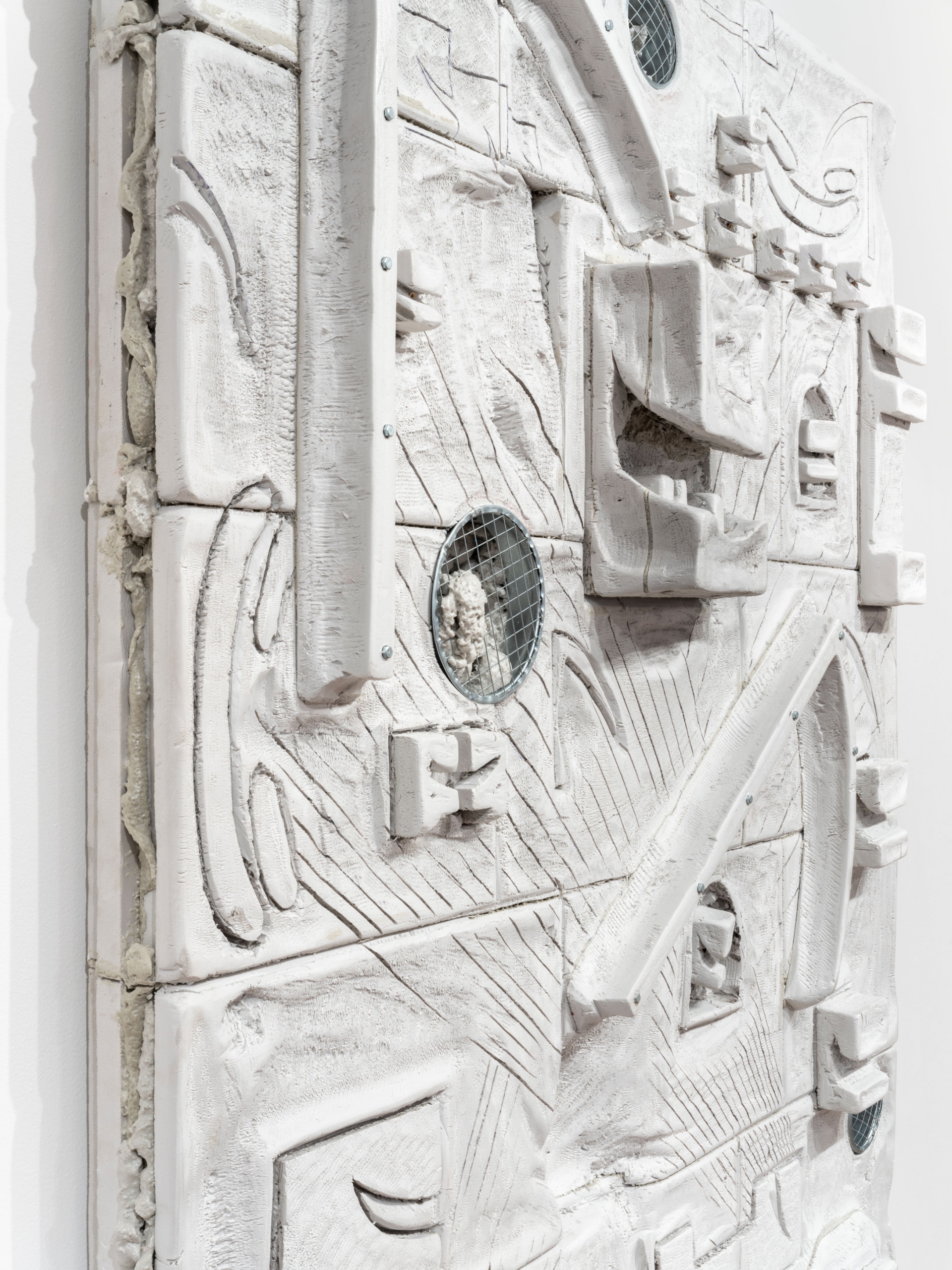

There has been much talk of the apocalyptic aesthetic of Cezary Poniatowski’s works in relief, made of imitation leather, carpets, extruded polystyrene or insulation foam. This is science fiction conveyed by forms and objects often codified as coming from Eastern Europe. Through the prism of memory, symbols and a sardonic sense of humour, these reliefs describe a technocratic world, awaiting transformation.

In Peng Zuqiang’s film The Cyan Garden, 2022, collective history and personal stories intertwine. The image rotates around a former clandestine radio station, active from 1969 to 1981, now supposedly a hotel. “Voice of the Malayan Revolution” can be heard before the protagonist flips the switch to select a romantic song and continue cleaning an Airbnb apartment, with a traditional décor, somewhere, in another town, drifting between the past and the present.

« it was a hot day, a day that was blue all through » lit-on dans les premiers paragraphes d’Invitation au supplice de Nabokov, écrit en 1932. C’est le roman le plus poétique de l’écrivain, selon ses propres mots. Une histoire dystopique où le personnage principal — prisonnier dans l’attente de l’exécution de sa sentence — invente un monde imaginaire fait de métaphores et d’allusions. Où la journée peut devenir bleue, le geôlier peut valser et l’araignée parler. La fin controversée du roman suggère que le prisonnier échappe à la peine grâce à l’imagination, qui le transporte dans un voyage entre l’espace et le temps. Azar Nafisi analyse ce livre dans son roman autobiographique — Lire Lolita à Téhéran (2002). Alors qu’elle enseigne la littérature occidentale à l’Université de Téhéran pendant la révolution de 1979, elle prône la force de la fiction et son pouvoir transcendant. Elle décrit comment, sous un regime qui anéantit les métaphores et les allusions, la compréhension des histoires et de la littérature s’atrophie. La fiction devient plate et banale pour servir une cause et les nuances de la narration disparaissent.

Oser poser une image, tenir le réel à distance, s’en affranchir, le nier est un moyen de liberté créé par les artistes. La fiction persiste dans les œuvres d’art malgré le flou chaotique des nouvelles données, malgré le bruit perpétuel et monotone. Les histoires, les métaphores et les récits imaginaires sont au cœur de cette exposition.

Sur les toiles d’Inès di Folco Jemni apparaissent des univers inter-galactiques, puisant dans les références de toutes cultures confondues. Dans sa peinture à l’huile rehaussée de térébenthine de Venise et de paillettes, se dessinent des personnages imaginaires, aux traits féminins, qui voyagent dans un espace fictif, indéterminé. On y voit des détails de villes aux architectures médiévales, des fleurs magiques, parfois carnivores, des fées, des couchers de soleil, violets, denses. Une atmosphère de rite sacré se propage entre Message, Souvenir et Médina.

Ladji Diaby crée dans ses sculptures un nouveau langage très personnel, lié à son environnement domestique, en relation directe avec ses origines. Il y est toujours question d’objets et d’images, qu’il utilise par transferts — une technique qu’il applique dans ces œuvres, pour parler de la spiritualité, des émotions, des sentiments, des idoles, mais aussi de l’absurdité des récits officiels et imposés.

L’œuvre de Tomasz Kowalski oscille librement entre les différentes époques et styles de l’histoire de l’art, tout en produisant une iconographie où se développe son imagination personnelle et fragmentée. Il détruit la hiérarchie entre le sommeil, le rêve et l’état de veille en célébrant la liberté de l’inconscient. Ses personnages semblent parfois disparaître dans la profondeur de la couleur. En collaboration avec avec sa mère Alicja Kowalska, artiste textile, Tomasz Kowalski développe aussi la technique de la tapisserie.

On parle souvent de l’esthétique apocalyptique des œuvres-reliefs de Cezary Poniatowski, produites en faux cuir, en tapisserie, en polystyrène extrudé ou en mousse à canon. C’est la science-fiction qui se traduit par les formes et les objets souvent codifiés comme venant de l’Europe de l’est. À travers le prisme de mémoire et des symboles, d’humour sardonique, ces reliefs décrivent un monde technocrate, en attente de transformation.

Dans le film The Cyan Garden, 2022, de Peng Zuqiang se croisent l’histoire collective et des histoires personnelles. L’image tourne autour d’une ancienne station radio clandestine, active entre 1969 - 1981, censée être devenue un hôtel aujourd’hui. On entend « Voice of the Malayan revolution » avant que le protagoniste ne tourne l’interrupteur pour choisir une chanson romantique et continuer à nettoyer un appartement airbnb, au décor traditionnel, quelque part, dans une autre ville, fondue entre le passé et le présent.

Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2022, oil and gouache on linen, 146 × 116 × 2 cm

Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2022

Inès Di Folco Jemni, Message, 2023, oil on canvas, 100 × 100 cm

Inès Di Folco Jemni, Message, 2023

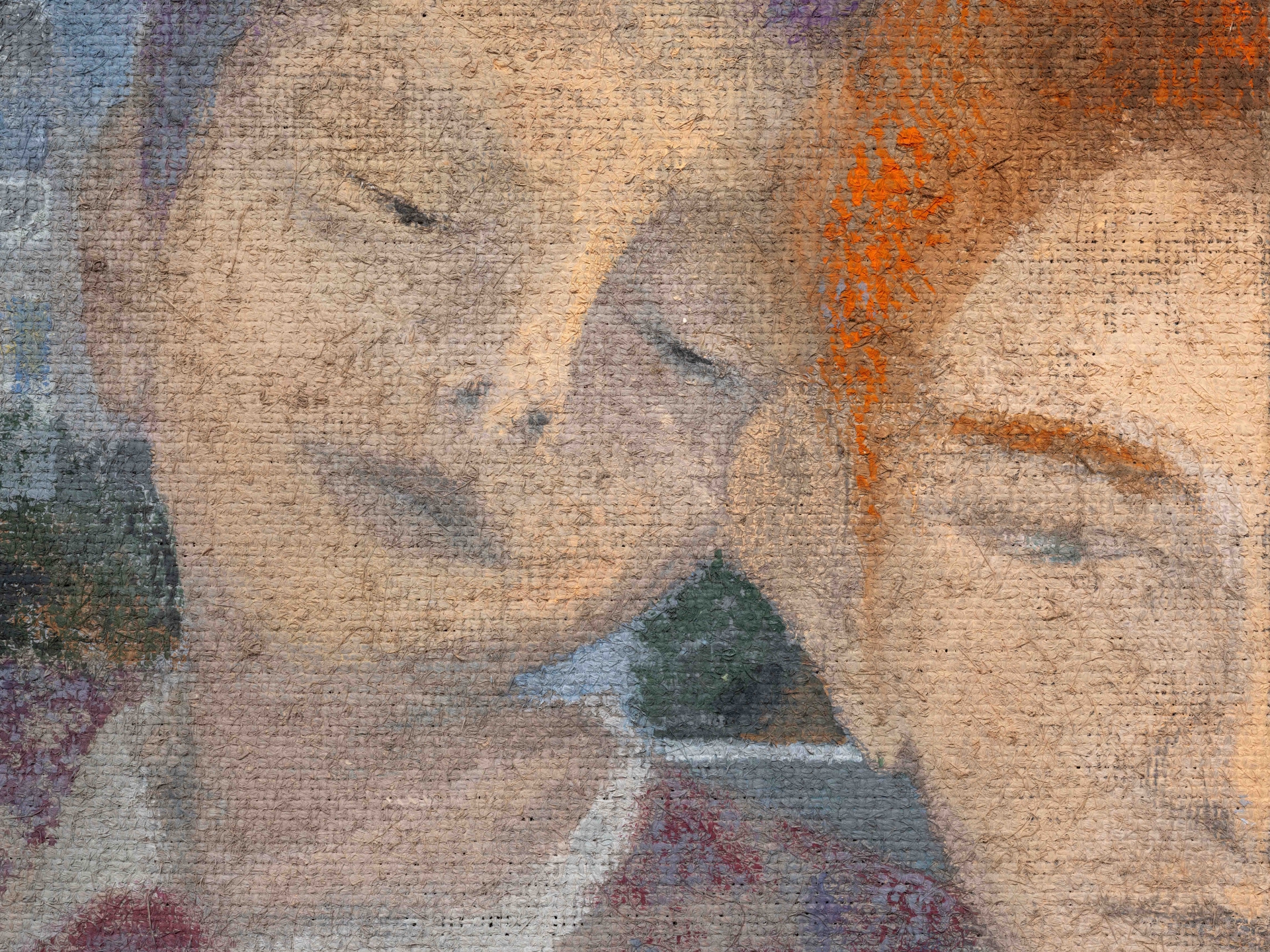

Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2024, gouache and oil on jute, 42 × 32 cm

Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2024

Detail

Ladji Diaby, Untitled, 2024, mixed media, 92.5 × 130 × 36 cm

Ladji Diaby, Untitled, 2024, mixed media, 92.5 × 130 × 36 cm

Detail

Ladji Diaby, Untitled, 2024

Detail

Cezary Poniatowski, Guardians of Sleep, 2024, extruded polystyrene, metal vents, gunfoam, 175 × 130 × 25 cm

Cezary Poniatowski, Guardians of Sleep, 2024, extruded polystyrene, metal vents, gunfoam, 175 × 130 × 25 cm

Cezary Poniatowski, Guardians of Sleep, 2024

Detail

Cezary Poniatowski, Domesticated, 2024, faux leather, upholstery foam, carpet, screws, metal zip ties, wood, binoculars, 70 × 60 × 15 cm

Cezary Poniatowski, Domesticated, 2024

Cezary Poniatowski, Domesticated, 2024

Detail

Inès di Folco Jemni, Médina, 2023, oil on cardboard, 50 × 40 cm (51.5 × 42 cm framed)

Inès di Folco Jemni, Médina, 2023

Detail

Inès di Folco Jemni, Souvenir, 2024, oil on canvas, 100 × 100 cm

Ladji Diaby, Untitled, 2023, mixed media, 82 × 58 × 58 cm

Ladji Diaby, Untitled, 2023

Ladji Diaby, Untitled, 2023

Detail

Alicja Kowalska & Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2021-2022, tapestry — sisal, wool, 2 panels : 140 × 130 cm (each)

Alicja Kowalska & Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2021-2022

Alicja Kowalska & Tomasz Kowalski, Untitled, 2021-2022

Detail

Peng Zuqiang, The Cyan Garden, 2022, single channel, color & BW, 16 mm transferred to HD video, 8 min 5 sec

Peng Zuqiang, The Cyan Garden, 2022

Peng Zuqiang, The Cyan Garden, 2022, single channel, color & BW, 16 mm transferred to HD video, 8 min 5 sec

Excerpt

Thanks to the artists and Antenna Space, Dawid Radziszewski, Sissi Club, Wschód Gallery and 15 Orient.

Exhibition views, it was a hot day, a day that was blue all through, 5 & 7 rue de Beaune, Paris — Photos: Martin Argyroglo

PARIS — Cascades

9 rue des Cascades

75 020 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

PARIS — Beaune

5 & 7 rue de Beaune

75 007 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

Contact

PARIS — CASCADES: +33 (0)9 54 57 31 26

PARIS — BEAUNE: +33 (0)9 62 64 38 84

info@galeriecrevecoeur.com