In Josephine the Singer, or The Mouse Folk, Kafka’s final text and testamentary work, written in 1923, he described the practice of an art lacking in virtuosity, produced by a population of mice that know nothing about history. There can be seen in it a metaphor for art and we can perceive a description of the mutations which the figure of the artist would undergo during the 20th century. Bolaño’s El policia rata (also a testamentary work, whose hero is a distant nephew of Josephine) adopts the same literary approach. A rat policeman investigates an improbable ‘raticide’: “rates don’t kill rats”. Meanwhile, Vinciane Desprès’ Autobiography of an Octopus evokes the existence of an animal literature. Octopi create language through their camouflage strategies: the ink sprays they eject to delude their predators remain “suspended in the water, forming a rather dense ball, finishing in a kind of tail”, thus leading any pursuers to “mistake their prey for a shadow”. Ink does not just conceal, it shows something different, in a deliberate form of expressiveness.

While on the look-out for stories that are both “speculative and realistic fabulations”, as Donna Haraway puts it, do authors and artists seek in this way a moral or other stories found among animals, which cannot be seen in our human past or projected in our human future?

Special thanks to the artists and Galerie 1900-2000, BQ, Carlos/Ishikawa, Chapter NY, KARMA, KOW, Lucas Hirsch, Nonaka-Hill, Sadie Coles HQ.

Matthew Barney, Ann Craven, Christopher Culver, Oscar Dominguez, Sophie Gogl, Ulala Imai, Alain Jacquet, Renaud Jerez, Ernst Yohji Jaeger, Jochen Lempert, Jannis Marwitz, Wolfgang Matuschek, Stuart Middleton, Ad Minoliti, Yu Nishimura, Francis Picabia, Autumn Ramsey, Louise Sartor, Michael E.Smith

La proie et l'ombre7 rue de Beaune, Paris

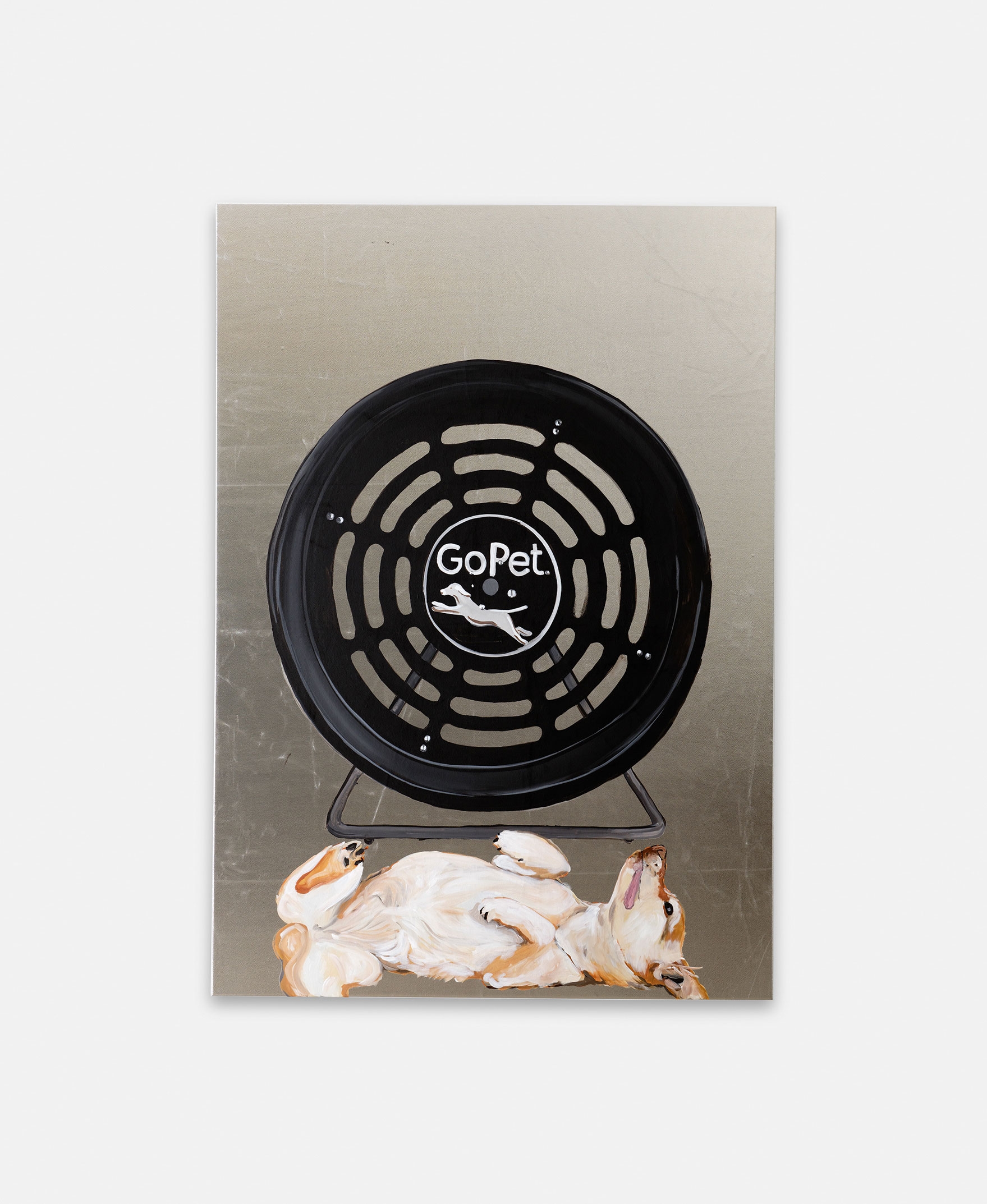

Jannis Marwitz, Projections, 2022

Oil in aluminium, 30 × 25 cm.

Dans Joséphine la Cantatrice ou Le peuple des souris, dernier texte et oeuvre testamentaire écrite en 1923, Kafka décrit la pratique d’un art sans virtuosité, fruit d’un peuple de souris qui ignore l’histoire. On peut y voir une métaphore sur l’art et y déceler la description des mutations que connaîtra la figure de l’artiste au cours du XXème siècle. El policia rata de Bolaño (également une œuvre testamentaire et dont le héro est le lointain neveu de Joséphine) s’inscrit dans la même lignée littéraire. Un policier rat enquête sur un improbable raticide: « les rats ne tuent pas les rats ». Dans l’Autobiographie d’un poulpe de Vinciane Desprès, est évoquée l’existence d’une littérature animale. C’est par leurs stratégies de camouflage que les poulpes engendrent le langage: les jets d’encre lancés afin de leurrer les prédateurs restent “en suspension dans l’eau et forment une boule assez dense terminée par une sorte de queue” menant ainsi son poursuivant à “prendre la proie pour l’ombre. » L’encre ne fait pas que cacher, elle montre autre chose: une forme d’expressivité délibérée.

En quête d’histoires qui soient à la fois « des fabulations spéculatives et des spéculations réalistes » comme le précise Donna Haraway, les auteurs et les artistes cherchent-ils ainsi une morale ou d’autres histoires chez les animaux qu’ils ne trouvent plus dans notre passé humain ?

Merci aux artistes et aux Galerie 1900-2000, BQ, Carlos/Ishikawa, Chapter NY, KARMA, KOW, Lucas Hirsch, Nonaka-Hill, Sadie Coles HQ.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2019

Airplane chair, plastic and bees, 70 × 50 × 60 cm.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2019, detail.

Renaud Jerez, AA5, 2015

Textile and foam, variable dimensions.

Sophie Gogl, Untitled, 2022

Acrylic on leather, 160 x 120 cm.

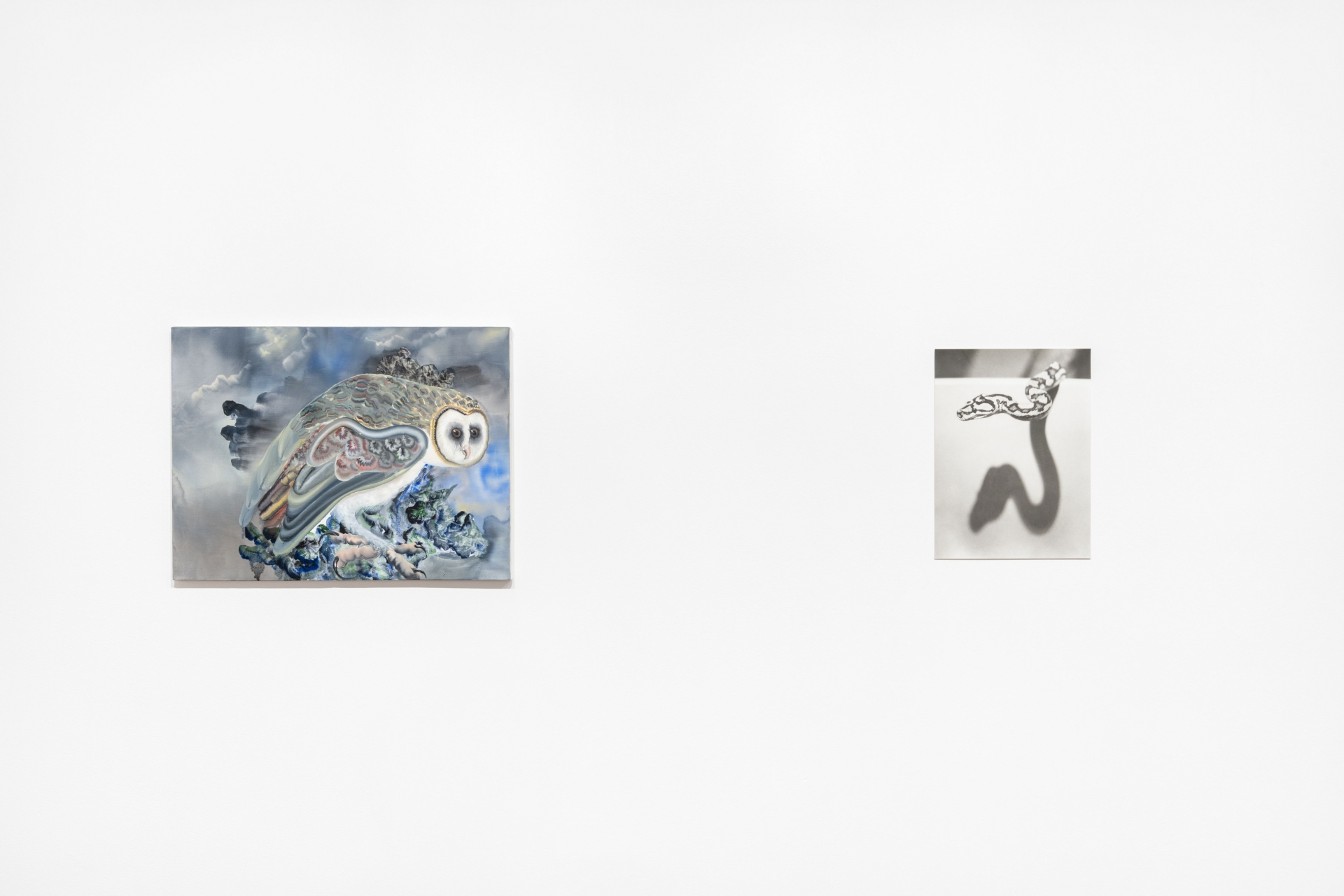

Ann Craven, Snowy Owls (after Abudon, January 2, 2021), 2021

Watercolour on arches paper, 76,2 × 55,9 cm / 81,3 × 61 cm (framed).

Francis Picabia, Untitled, 1937

Oil on panel, 30 × 30 cm.

Autumn Ramsey, See, 2016, oil on canvas, 46 × 61 cm.

Jochen Lempert, Schlatten / Schlange, 2022, silver gelatin print, 38 × 28,3 cm.

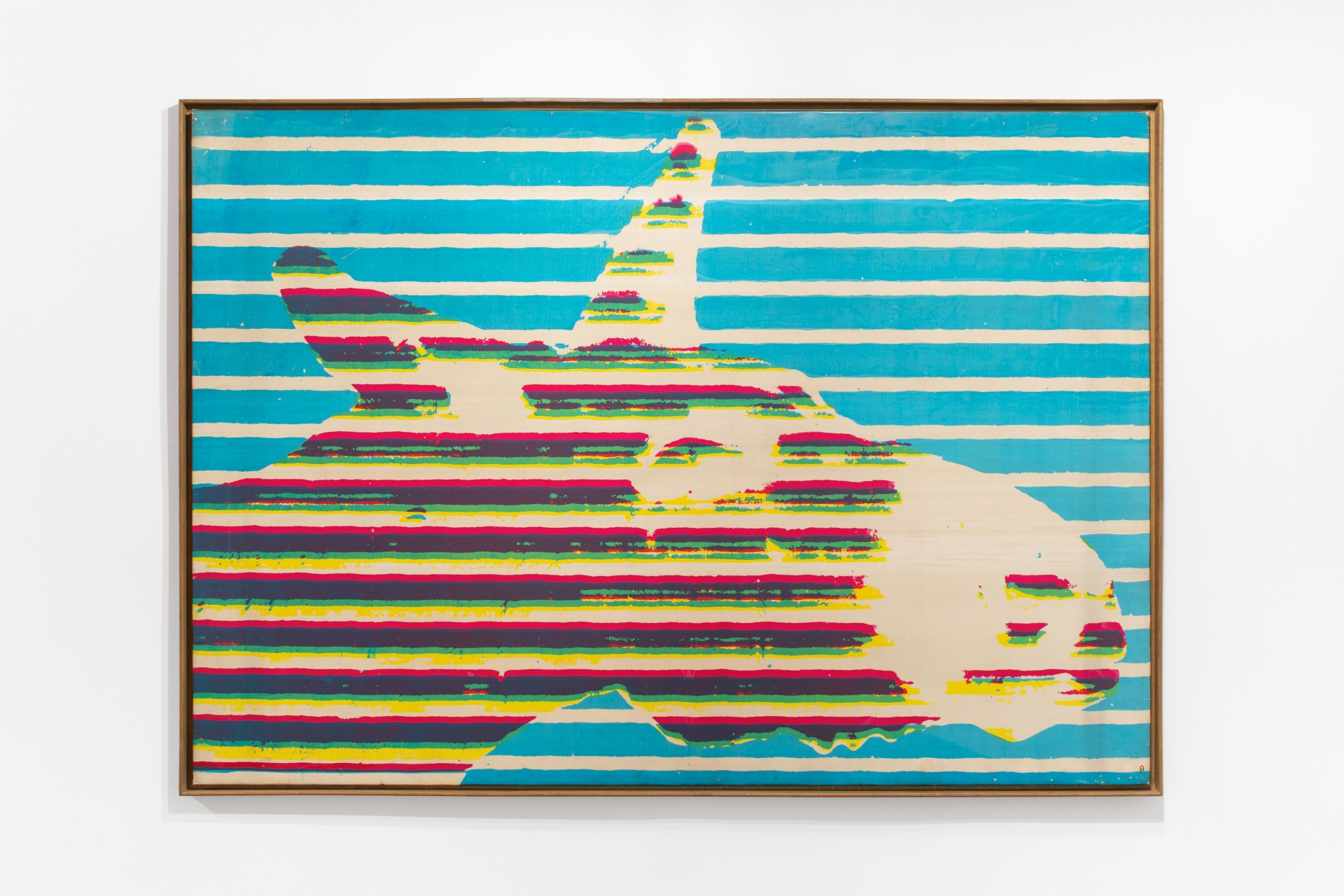

Alain Jacquet, Ane, 1966

Quadrichromy on canvas, 114 × 164 cm.

Oscar Dominguez, Untitled, 1948

Ink on paper, 26 × 21 cm.

Matthew Barney, Nomono Apu and Iron Man, 2020

Graphite and gouache on paper in high-density polyethylene frame, 48,3 × 40 × 3,2 cm (framed).

Ad Minoliti, Oso, 2022

Acrylic and print on canvas, 120 × 150 cm.

Stuart Middleton, G09, 2021, coloured pencil on paper, 48 × 69,5 × 2,5 cm (framed).

Yu Nishimura, look back, 2022, tempera on canvas, 80,3 × 65,2 cm.

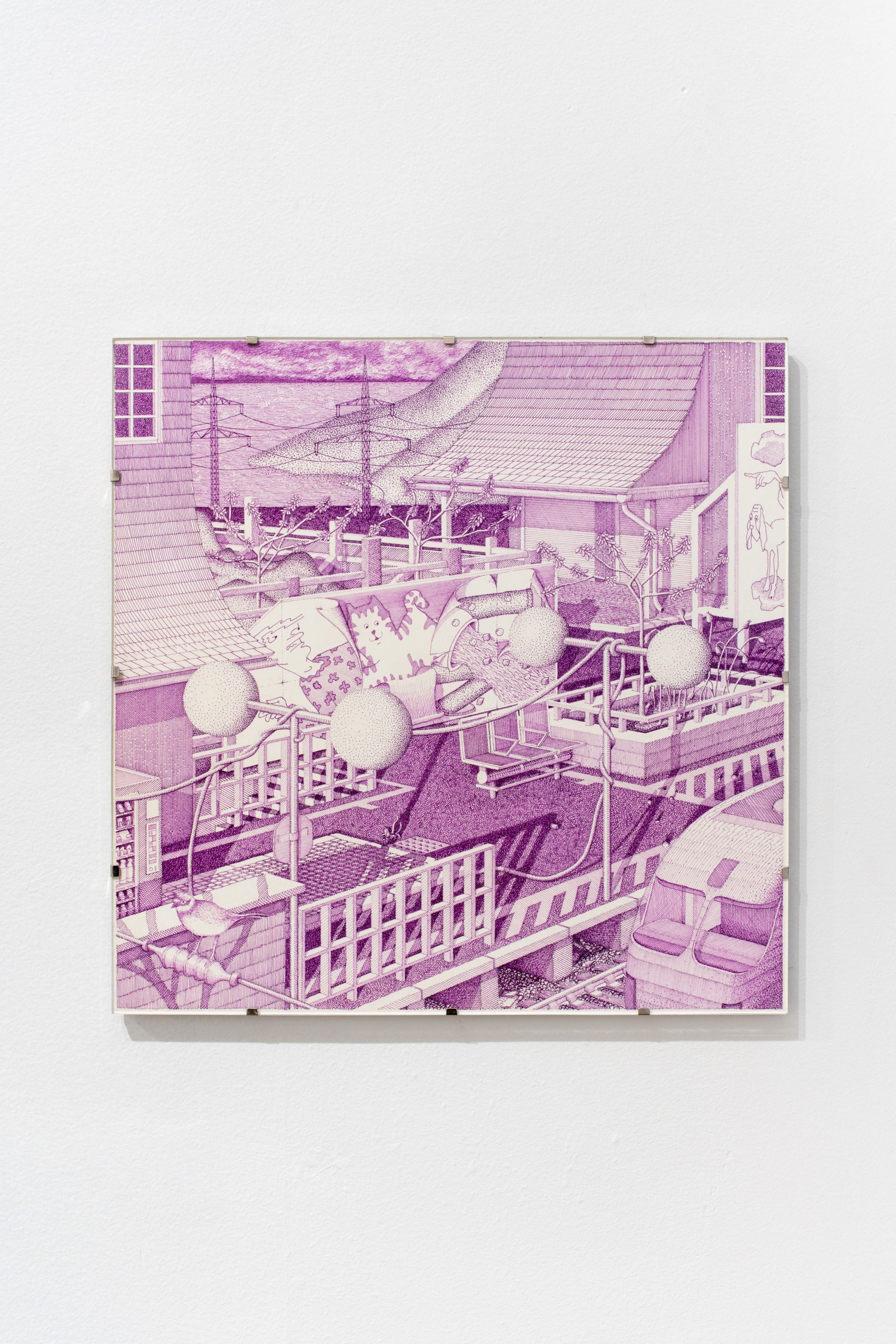

Wolfgang Matuschek, Afternoon one, 2022

Ink on paper in aluminum uv glass clipframe, 30 × 30 cm.

Christopher Culver, Geese in Green Smoke, 2022

Charcoal and pastel on paper, 63,5 × 48,3 cm / 70 x 55 x 4 cm (framed).

Louise Sartor, Harebells, 2022

Acrylic on cardboard, 32 x 15,5 cm.

Ernst Yohji Jaeger, Untitled 3 (Bat), 2021

Oil on canvas, 30 × 30 cm.

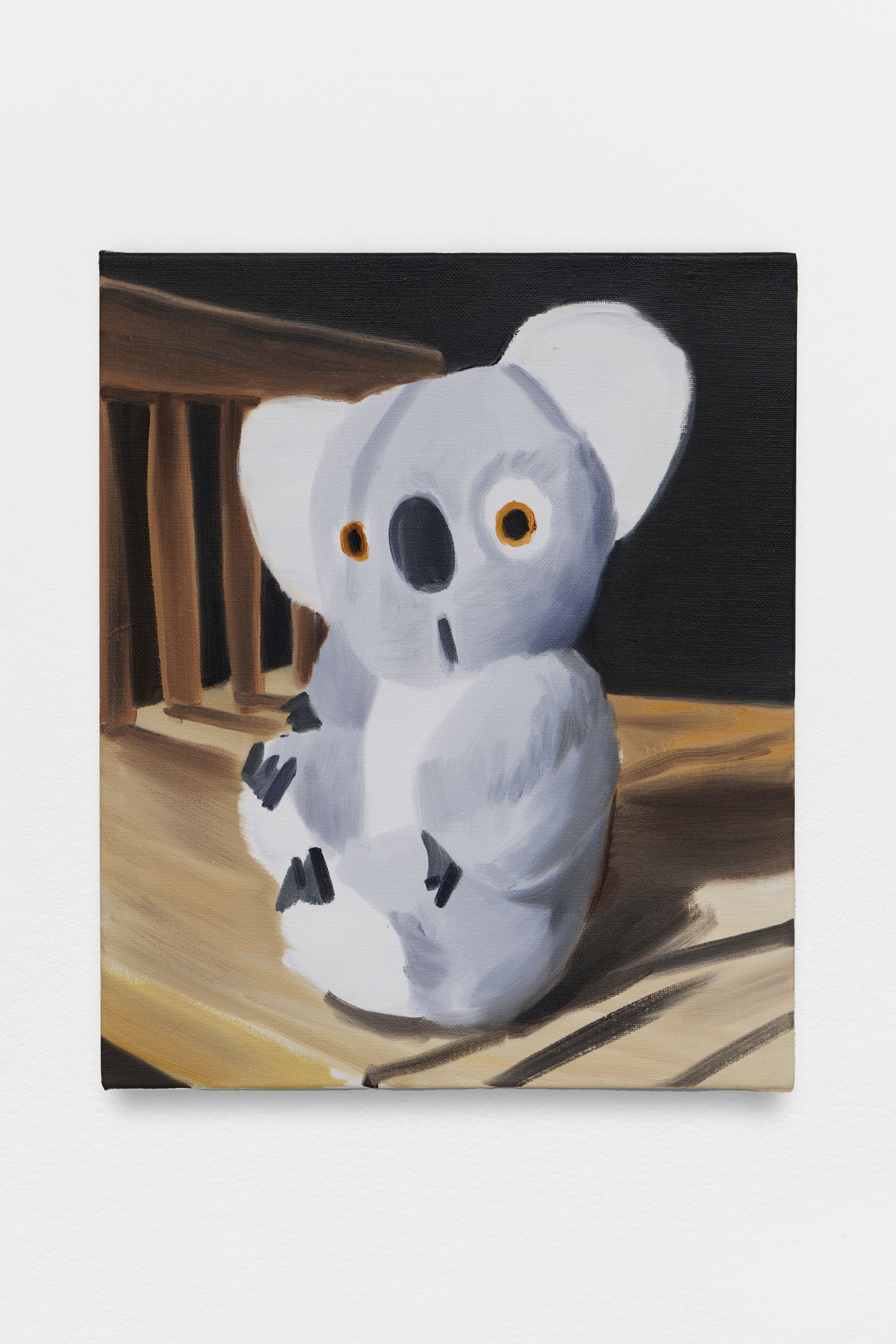

Ulalai Imai, Koala, 2022

Oil on canvas, 41 × 31,8 cm.

Photos:

Exhibition views & work views: Martin Argyroglo

Jannis Marwitz, Projections, 2022; Sophie Gogl, Untitled, 2022: Aurélien Mole

PARIS — Cascades

9 rue des Cascades

75 020 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

PARIS — Beaune

5 & 7 rue de Beaune

75 007 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

Contact

PARIS — CASCADES: +33 (0)9 54 57 31 26

PARIS — BEAUNE: +33 (0)9 62 64 38 84

info@galeriecrevecoeur.com