Nathaniel Mellors throws historical linearity off course by using anachronistic stylistic devices belonging to an imaginary cinematic world and objects indexed to contemporary archaeology. It is a matter of putting the crisis of the modern system into perspective, both in its artistic nature and its economy, which is reflected in Mellors’s hybridization of the contemporary and the Palaeolithic.

What crisis does Mellors refer to? To the failure of ideologies (progress, communism, universalism) established in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the beginning of the scientific era. The rupture between humanity and nature—‘leaving Eden’—during the Neolithic period with the advent of tool production, the domestication of animals and finally the mastery of agriculture that enabled the storage of goods and the beginning of capitalism. Or the realization of the modern subject as being “in crisis”, that is, permanently on the brink, or “too early” or “too late” in the fold of time, the breaking of the image, the temporal coalescence that defines our present. Mellors creates a layered history, a meta-historical voyage with humorous facets, an original quest.

The film Neanderthal Crucifixion (2021) takes place inside a hemispheric cavity. In the matrix. Projections on white-plastered walls constitute a set of panels, screens and folding screens. They are stop-motion images. The whole installation seems to be an enlarged model, the figurative prototype of which is a plasticine figure. It’s sausage-shaped head sits horizontally on it’s a trunk-body, forming a T. The sculptural forms seem to be in the spirit of the work of Peter Fischli & David Weiss, combining a DIY aesthetic with found objects, or the installations of Jason Rhoades and their horror vacui principle. From the infinitely small to the infinitely large.

The cave, whose size and depth is uncertain, appears to have been whitewashed. It is filled with projected images, generated using Google’s ‘Deep Dream’ algorithm applied to images of Chauvet cave and other sources. […] These appear haloed by dotted lines, pixels and coloured frames. A new pictorialism built upon the use of edited found images is at work. Thus all this was produced, potentially, by an algorithm or Artificial Intelligence. Glitch or glyph?

We credit the whole invention of symbolism and art to Homo Sapiens. However, recent discoveries, such as an engraved bone in Lower Saxony’s Unicorn Cave (Einhornhöhle), prove “decorative” artistic activity was in existence at the remote date of 51,000 BCE; that is, well before the junction of Neanderthal and Sapiens. This fits with certain recent historical sources that describe prehistoric artists’ nomadism, giving evidence of schools of style, and thus, of notions of transmission. Decorated caves could be artist’s studios or sites that punctuated an initiatory journey.

This defies the idea of progress in art, which is always searching for evolution, starting from representation as a copy of the real. In reality, figuration and abstraction have always coexisted. Dots, lines, blown pigment, bison, erect men, vulvas: all these motifs can be found on cave walls. We also suppose that there is a connection between the use of caves, rock decoration and sources of light—daylight, fire, torches—and the intentional exploitation of crevices to create surprise effects. Rock caves could well be a form of proto-cinema. […] Recent discoveries also point to the fact that Neanderthal man was certainly nomadic, but socially organized, and that inequalities already existed in the Palaeolithic period.

— Marie de Brugerolle

Nathaniel Mellors

BrowsererCrèvecœur, Paris

Nathaniel Mellors déjoue la linéarité historique par son usage anachronique de figures de style appartenant à un imaginaire cinématographique et d’objets indiciels relevant d’une archéologie contemporaine. Il s’agit de la mise en perspective de la crise du système moderne, tant dans sa nature artistique que dans son économie. L’hybridation du contemporain et du paléolithique en est le reflet.

De quelle crise s’agit-il ? Celle de la faillite des idéologies (progrès, communisme, universalisme), mises en place au dix-neuvième et vingtième siècle, début de l’ère scientifique. La scission de l’homme et de la nature, sortie de l’Eden que serait le néolithique, avec le début de la production d’outils puis la domestication animale et enfin la maîtrise de l’agriculture, permit le stockage de biens, et le début du capitalisme. Ou bien encore la réalisation du sujet moderne comme être « en crise », c’est-à-dire sans cesse sur la brèche, ou « trop tôt » ou « trop tard », dans le pli du temps, la fracture de l’image, la coalescence temporelle qui qualifie notre présent. C’est une Histoire feuilletée et sous des aspects drolatiques, une traversée métahistorique, une quête originelle.

La vidéo Neanderthal Crucifixion (2021) se passe à l’intérieur d’une cavité hémisphérique. Dans la matrice. Des projections sur des murs enduits à la chaux constituent un ensemble de panneaux, écrans, paravents. Ce sont des images en stop motion. L’installation semble une maquette agrandie, dont le prototype figuratif est constitué par un personnage en pâte à modeler. Sa tête est une forme de saucisse posée de manière horizontale sur un tronc-corps, formant un T. On pense aux dispositifs de Fischli & Weiss, combinant une esthétique du bricolage à partir d’objets trouvés ou encore aux installations de Jason Rhodes. De l’infiniment petit à l’infiniment grand.

La grotte, dont la taille et la profondeur sont incertaines, semble avoir été blanchie à la chaux. Elle est remplie d’images projetées, générées à l’aide de l’algorithme Deep Dream de Google appliqué à des images de la grotte Chauvet et d’autres sources. […] Spirales et zigs zags psychédéliques apparaissent comme des hallucinations. Ce sont les approximations générées par le programme de vision par ordinateur créé par Google. Celui-ci utilise un système qui reconstitue un réseau neuronal convolutif (en strates) basé sur un algorithme. Surnommé Inception, ce réseau repère la structure des images qu’il reconstitue par stimuli, imitant le fonctionnement de notre système de reconnaissance. Le cerveau cherchant à créer du sens par assimilation de formes aléatoires, cela créé un phénomène de paridolie , qui donne une apparence hallucinogène aux images. C’est donc un algorithme ou une Intelligence Artificielle qui aurait potentiellement produit tout cela. Glitch ou glyphe ?

On attribue l’invention du symbolique et de l’art à l’Homo Sapiens. Or, les découvertes récentes prouvent l’activité artistique « décorative » à la date reculée de -51 000 ans, c’est à dire bien avant la jonction Néandertal/Sapiens. Cela rejoint certaines sources historiques récentes, évoquant le nomadisme des artistes préhistoriques attestant des écoles de styles, donc de la notion de transmission. Les grottes ornées pourraient être des ateliers d’artistes et lieux ponctuant un parcours initiatique.

Ceci met en défaut la notion de progrès en art, qui voudrait une évolution à partir de la représentation comme copie du réel. Or, figuration et abstraction ont toujours coexisté. Points, lignes, souffles, bisons, hommes érectiles, vulves sont autant de motifs que l’on retrouve sur les murs. On suppose par ailleurs l’usage des grottes et des décors rupestres en lien avec les sources lumineuses naturelles ou non (lumière du jour, feu, torches) et l’utilisation intentionnelle des anfractuosités à des fins d’effet de surprise. Les grottes rupesres seraient des formes de proto-cinéma. […] Les découvertes récentes démontrent aussi que l’homme de Néandertal était certes nomade, mais sans doute organisé socialement, et que les inégalités existaient déjà au paléolithique.

— Marie de Brugerolle

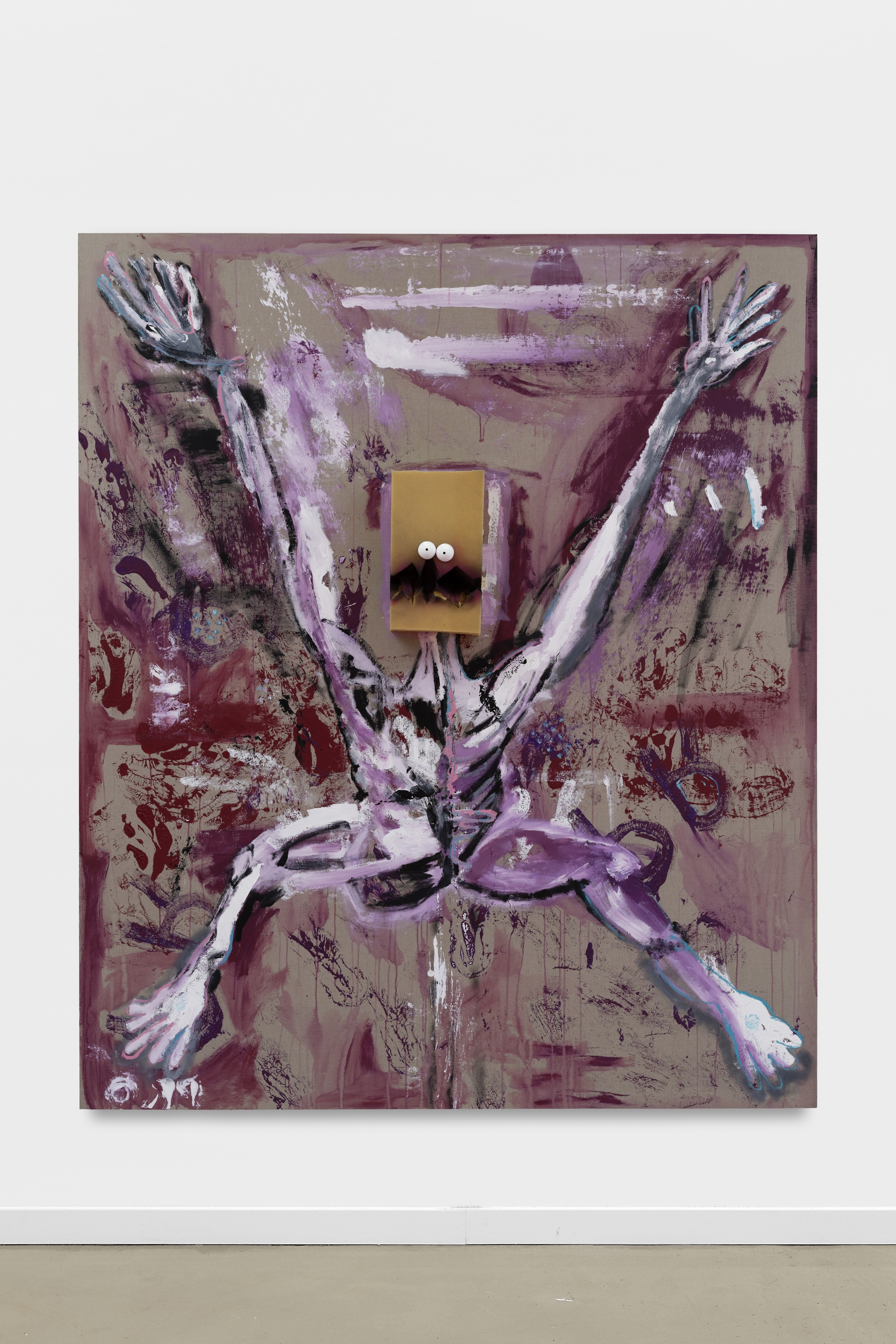

Nathaniel Mellors, Purple Crucifixion Painting, 2021, acrylic and floor paint, sponge, polystyrene, and spray paint on canvas, 230 × 195 cm.

Nathaniel Mellors, Purple Crucifixion Painting, 2021, acrylic and floor paint, sponge, polystyrene, and spray paint on canvas, 230 × 195 cm. Deatil.

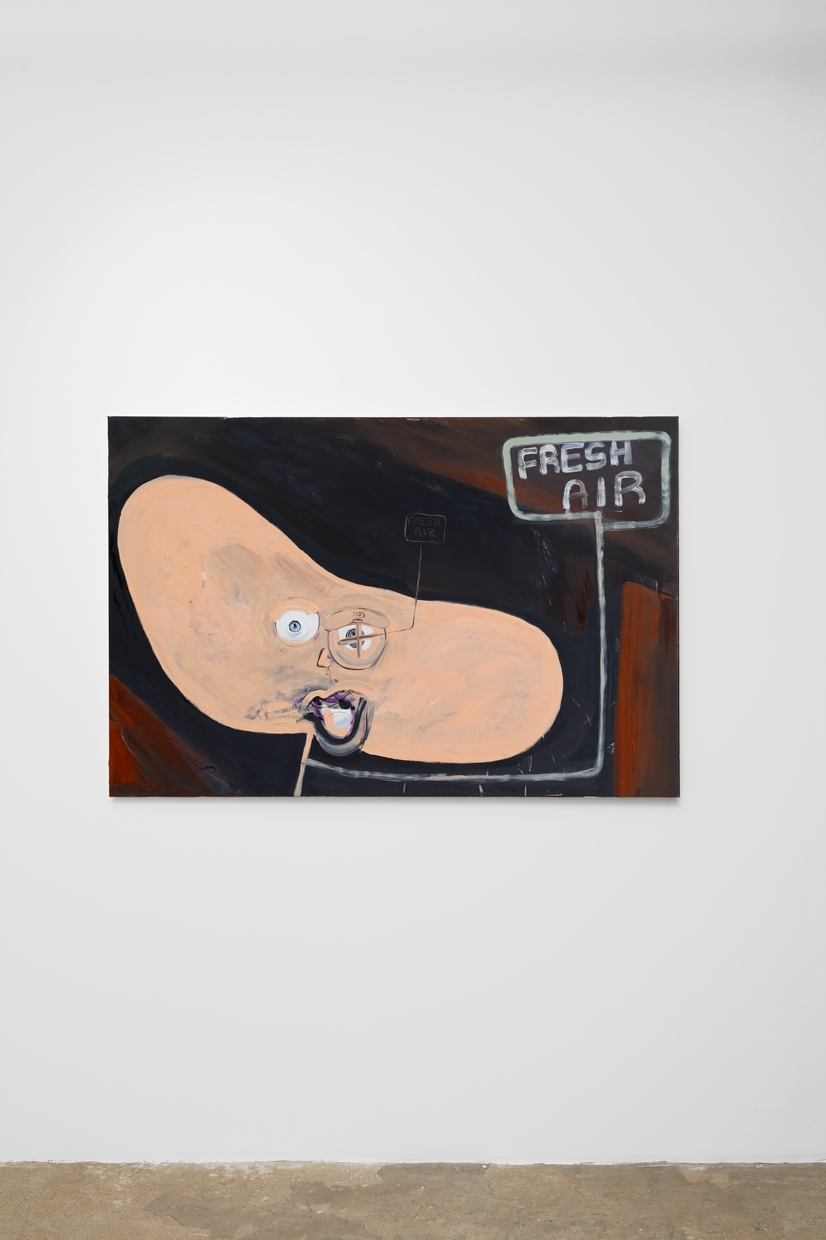

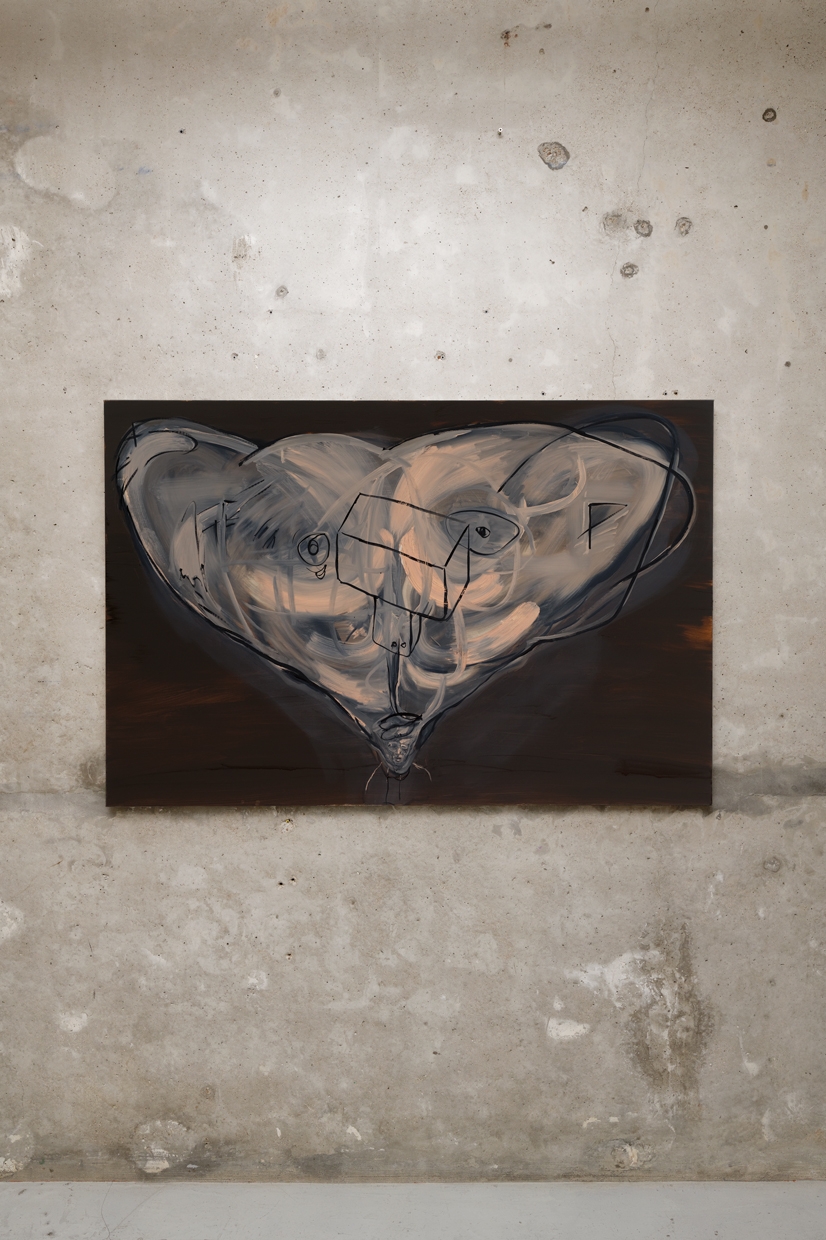

Nathaniel Mellors, Brow #1 (Fresh Air), 2021, oil on canvas, 102 x 152 cm.

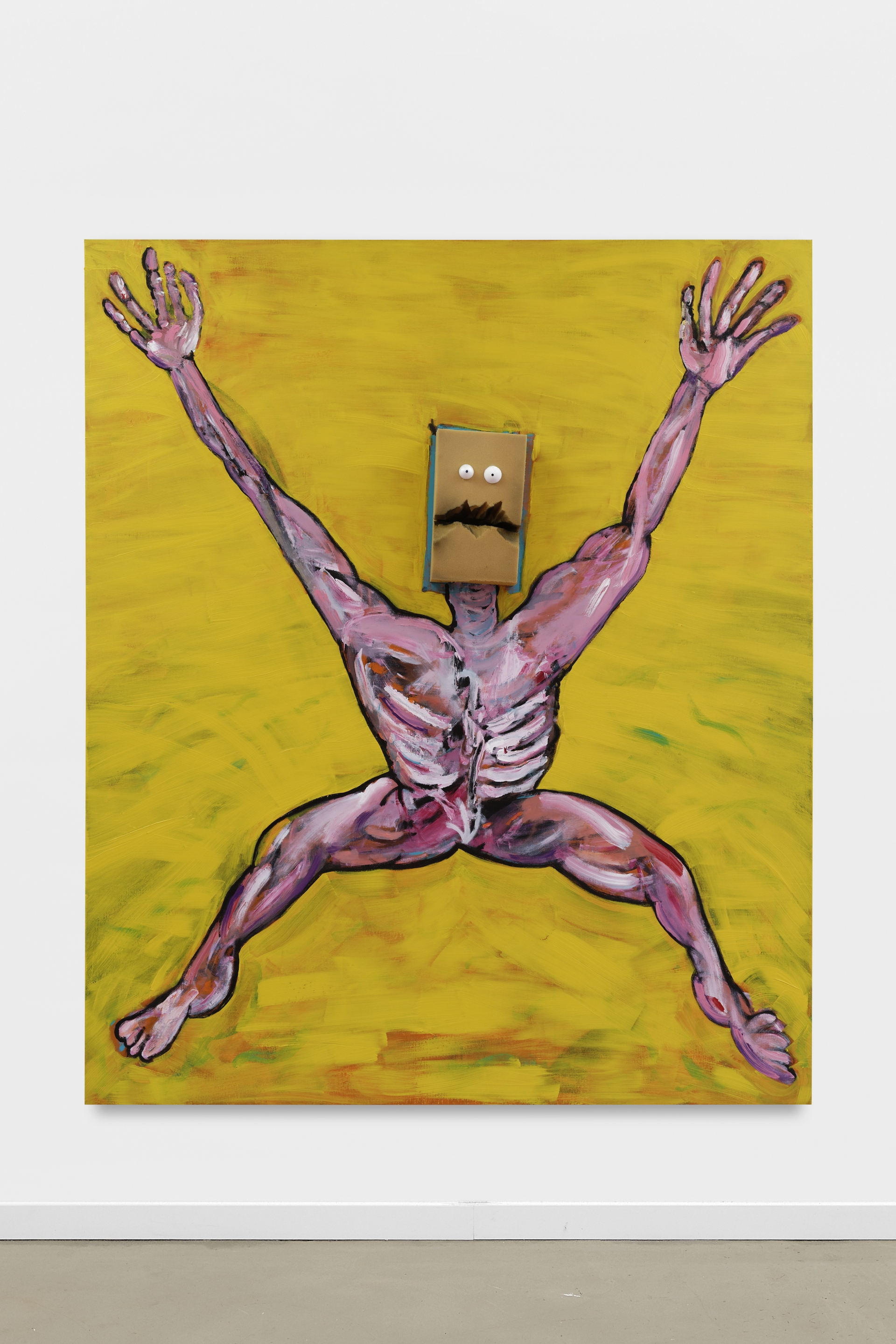

Nathaniel Mellors, Yellow Crucifixion Painting, 2021, acrylic and floor paint, sponge, polystyrene, and spray paint on canvas, 230 × 195 cm.

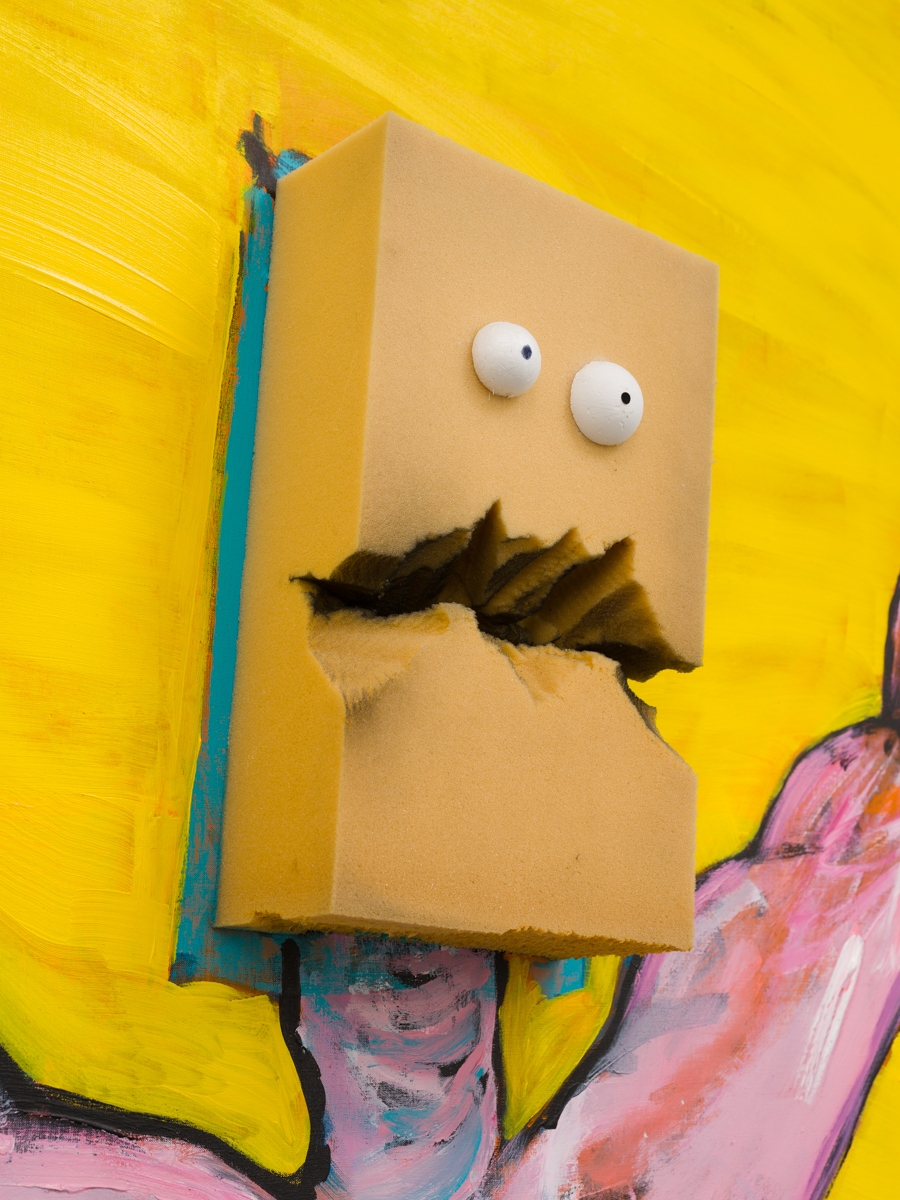

Nathaniel Mellors, Yellow Crucifixion Painting, 2021, acrylic and floor paint, sponge, polystyrene, and spray paint on canvas, 230 × 195 cm. Detail.

Nathaniel Mellors, Dolorous Figure (Tepe), 2021, oil on canvas, 102 x 152 cm.

Photographs by Aurélien Mole.

PARIS — Cascades

9 rue des Cascades

75 020 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

PARIS — Beaune

5 & 7 rue de Beaune

75 007 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

Contact

PARIS — CASCADES: +33 (0)9 54 57 31 26

PARIS — BEAUNE: +33 (0)9 62 64 38 84

info@galeriecrevecoeur.com