Michael E. Smith

invited by Cédric Fauq

Defying Gravity

The first time I visited Capc in Bordeaux, where I currently work, was during the Christmas holidays in 2013. I was staying a few days with the parents of my roommate in Vincennes, Elsa. At that moment, I was just days away from starting an internship at the Centre for Art and Landscape on the Vassivière Island, assisting with dismantling an exhibition by Fernanda Gomes and installing one by Sheela Gowda («Open Eye Policy»). A few weeks later, I would begin another internship at the galerie Crèvecœur, at 4 Rue Jouye-Rouve, which was showing, at the time, Renaud Jerez («Adideath»). I had managed to negotiate skipping some of the bachelor degree classes to be able to work.

During that first visit to the Capc, one of the exhibitions on display was a solo by the American artist Michael E. Smith, invited by Alexis Vaillant. It was held in the side galleries on the ground floor. By then, I was not familiar with the artist’s practice and I wouldn’t immediality register his name. But impressions of his exhibitions lingered with me—particularly that of a baby car seat suspended on the wall, refracted by a decomposed, multicolored halo of light. By the end of 2014, I would encounter his work again—this time at Crédac in Ivry, in an exhibition curated by Chris Sharp («THE REGISTRY OF PROMISE 3 – The Promise of Moving Things»). It felt like recognizing someone’s face without being able to recall where and when we had met.

One of the works he exhibited there was installed in the art center’s entrance, on the ceiling: both the first and last piece of the show. Composed of a tangle of cables and computer connectors, its tentacle-like appearance reminded me of Marvel’s Venom. Chris Sharp wrote about Michael E. Smith’s work that it «emanates an eerie impression of the human body, something akin to possession.»

The following year, in 2015, as I moved to London and started another internship with Vincent Honoré at the David Roberts Art Foundation, several works by Michael E. Smith were included in the group exhibition «Albert the kid is ghosting.» In a space on the outskirts of the central galleries, a bicycle frame laid on the ground, at the end of which was attached a bottle of pesticide («Spectracide: Wasp & Hornet Killer»): a prototype for an extinction machine. While Googling «Vincent Honoré Michael E. Smith,» I came across an interview Vincent had given to Trébuchet magazine in 2014. To the final question, «Who do you think is the artist to watch at the moment and why?» he answered: « At the moment, I am particularly looking at the sculptures and videos of Michael E. Smith. They translate a sense of loss and ruin which echoes, often with humour, our current state of idealogical uncertainty.»

This was followed by several «direct» encounters with the artist’s work (at KOW in Berlin, Modern Art in London, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and MoMA PS1 in New York), and a growing—though probably illusory—sense that I could decipher his language. I noticed recurring motifs, such as animals: stuffed, dried, skinned. Sometimes recognizable (a parrot, a pufferfish), other times transformed or abstract (columns of wings, furry cubes); the use of domestic furniture (sofas, chairs, tables); and manipulation of light—its removal (primarily) but also its addition (via lasers). Always present was a sense of life within the inert, and at times, a «pause» or «glitch,» a spasm.

For the 13th Baltic Triennial—on which I worked—I installed several works by Michael E. Smith at the CAC in Vilnius. The installation protocols, coupled with a FaceTime session with the artist and his assistant, helped me understand the importance he placed on balance, distance, gravity, and breathing (between the works themselves but not only). This installation experience coincided with the writing of the first text I wrote about his work—the only one to date. I then attempted to draw a parallel between the experience of flying over Detroit under snow and his exhibitions.

In recent years, several of Michael’s works have particularly struck me. One of them was a Pikachu plush toy stuck to a metal bar behind a window. A floating evicted Pokémon, left out in the street, seemingly ready to do anything to get back inside. This was at Paris Internationale in 2019, before the lockdowns. Another was two overturned kayaks that resembled, in the dim gallery of Modern Art in London, cetacean bones. I visited this exhibition with my then-boss, Sam Thorne. It was the first time I met Mike in person. As he hovered his hands over one of the two overturned kayaks, a heavy engine noise began, transforming into a high-pitched whale cry as his hand moved toward the opposite end of the vessel’s hull.

These past few days, I’ve spent several hours with Mike, often late into the night. Between conversations about the exhibition we were assembling and our lives, he shared music, images, and GIFs, as well as the name of an artist I didn’t know—Jim Drain—who now teaches his son. Memories of video games surfaced—particularly of a creature from the Mario universe called «Pokey.» A cartoon I hadn’t known («Beavis and Butt-Head») made me realize we weren’t of the same generation. The presence of basketballs also reminded me that I hadn’t touched one in ages (while images of works by David Hammons and Jeff Koons jostled in my mind). One evening, he also showed me an Instagram reel that had recently struck him. It featured a monkey on a leash playing fearlessly with a threatening cobra. The video was captioned, «When You Just Don’t Care About Problems Anymore 🤣. » The reel’s tagline read: “Unbothered.”

Cédric Fauq

Defying Gravity

C’est pendant les vacances de Noël 2013 que je me suis rendu pour la première fois au Capc, à Bordeaux, où je travaille actuellement – je passais alors quelques jours chez les parents de ma colocataire à Vincennes, Elsa. A ce moment-là, je suis à quelques jours de commencer un stage au centre d’art et du paysage de l’île de Vassivière en régie, pour démonter une exposition de Fernanda Gomes et installer celle de Sheela Gowda (« Open Eye Policy »). Quelques semaines plus tard je commencerai un autre stage à la galerie Crèvecoeur au 4 rue Jouye-Rouve, qui montre alors Renaud Jerez (« Adideath »). J’avais réussi à négocier de ne pas suivre tous les cours de la licence que je suivais pour travailler.

Lors de cette première visite du Capc, une des expositions programmées est celle de l’artiste américain Michael E. Smith, invité par Alexis Vaillant, qui prend place dans les galeries latérales du rez-de-chaussée. Artiste que je ne connaissais pas et dont je ne retiendrai pas tout de suite le nom, mais des impressions : notamment celles d’un siège auto pour bébé suspendu au mur, sur lequel un halo de lumière décomposé et multicolore se réfractait. Dès la fin de l’année 2014, je retrouverai son travail – cette fois-ci au Crédac à Ivry, dans une exposition du commissaire d’exposition Chris Sharp (« THE REGISTRY OF PROMISE 3 – The Promise of Moving Things »). Surgira le sentiment de reconnaître le visage de quelqu’un sans véritablement pouvoir se souvenir d’où et quand je l’ai rencontré.

L’une des œuvres qu’il montrait dans cette exposition était installée dans l’entrée du centre d’art, au plafond : à la fois la première et la dernière pièce. Constituée d’un ensemble de câbles et connectiques informatiques, son aspect tentaculaire me rappelait le Venom de Marvel. Chris Sharp écrivait au sujet du travail de Michael E. Smith qu’il « en émane une impression hallucinante de corps humain, de l’ordre de la possession ».

L’année d’après, en 2015, alors que j’emménage à Londres et commence un autre stage auprès de Vincent Honoré à la David Roberts Art Foundation, plusieurs œuvres de Michael E. Smith sont incluses dans l’exposition collective « Albert the kid is ghosting ». Dans un espace en périphérie des galeries centrales, un cadre de vélo est posé au sol, à l’extrémité duquel est fixé une bouteille de pesticide (« Spectracide : Wasp & Hornet Killer ») : un prototype de machine d’extinction. En cherchant sur Google « Vincent Honoré Michael E. Smith », je suis tombé sur un entretien que Vincent a accordé au magazine Trébuchet en 2014. A la dernière question : « Quel est, selon vous, l’artiste à suivre en ce moment et pourquoi ? » il répond : « En ce moment, je regarde particulièrement les sculptures et les vidéos de Michael E. Smith. Elles traduisent un sentiment de perte et de ruine qui fait écho, souvent avec humour, à notre état actuel d’incertitude idéologique. »

S’en suivront plusieurs expériences « directes » du travail de l’artiste (aux galeries KOW à Berlin et Modern Art à Londres, au Palais de Tokyo à Paris, ainsi qu’au MoMA PS1 à New York), et le sentiment croissant – mais sans doute illusoire – de pouvoir en déchiffrer la langue. J’y trouvais des motifs récurrents comme l’animal : empaillé, desséché, dépecé. Parfois reconnaissables (le perroquet, le poissons-globe) et d’autres fois métamorphosé ou abstraits (des colonnes d’ailes, des cubes en fourrure) ; l’utilisation de mobilier domestique (le canapé, la chaise, la table) ; la manipulation de la lumière : son retrait (surtout) mais également son ajout (par le laser). Et toujours, ce sentiment de vie dans l’inerte, et, parfois, la « pause » ou encore le « glitch », le spasme.

Pour la 13ème Baltic Triennale – sur laquelle j’ai travaillé – j’ai dû installer plusieurs œuvres de Michael E. Smith au CAC Vilnius. Les protocoles d’installation, couplés à un FaceTime avec l’artiste et un de ses assistants, m’ont alors fait comprendre l’importance que celui-ci accordait à l’équilibre, à la distance, à la gravité et à la respiration (entre les œuvres elles-mêmes mais pas seulement). Cette expérience de montage coïncidait avec l’écriture du premier texte que j’écrivais sur son travail – le seul jusqu’à aujourd’hui. J’y tentais de faire le parallèle entre l’expérience du survol de la ville de Détroit enneigée et celle de ses expositions.

Ces dernières années, j’ai été particulièrement marqué par plusieurs œuvres de Michael : l’une d’entre elle était une peluche de Pikachu collée à une barre de métal derrière une fenêtre. Un pokémon flottant, mis à la rue, qui semblait prêt à tout pour revenir à l’intérieur. C’était à Paris Internationale, en 2019, avant les confinements. Aussi, ces deux kayaks retournés, qui ressemblaient, dans l’espace éteint de la galerie Modern Art à Londres, à des os de cétacés. Je visitais cette exposition avec mon boss de l’époque, Sam Thorne. C’était la première fois que je rencontrais – en chair et en os – Mike. En faisant survoler ses mains au-dessus d’un des deux kayaks renversés, un son lourd de moteur s’enclenchait, pour se transformer en cri aigu de baleine, à mesure que sa main glissait vers l’extrémité opposée de la coque du vaisseau.

Ces derniers jours, j’ai passé plusieurs heures avec Mike, souvent tard le soir. Entre nos échanges sur l’exposition que l’on montait et nos vies, il m’a notamment partagé, entre plusieurs parts de pizzas, de la musique, des images et des gifs, le nom d’un artiste que je ne connaissais pas – Jim Drain – et qui enseigne maintenant à son fils. Des souvenirs de jeux vidéo sont remontés – en évoquant notamment une créature de l’univers Mario nommée « Pokey ». Un dessin-animé que je ne connaissais pas (« Beavis et Butt-head ») m’a fait réaliser que nous n’étions effectivement pas de la même génération. La présence de ballons de baskets m’a aussi rappelé que je n’avais pas touché un ballon depuis une éternité (en même temps que des images d’œuvres de David Hammons et Jeff Koons se bousculaient dans ma tête). Il m’a aussi montré, un de ces soirs, un reel instagram qui l’a particulièrement marqué dernièrement. On y voit un singe, en laisse, jouer avec un cobra menaçant, sans peur. Sur la vidéo on peut lire « When You Just Don’t Care About Problems Anymore 🤣». La légende du reel affiche : “Unbothered”.

Cédric Fauq

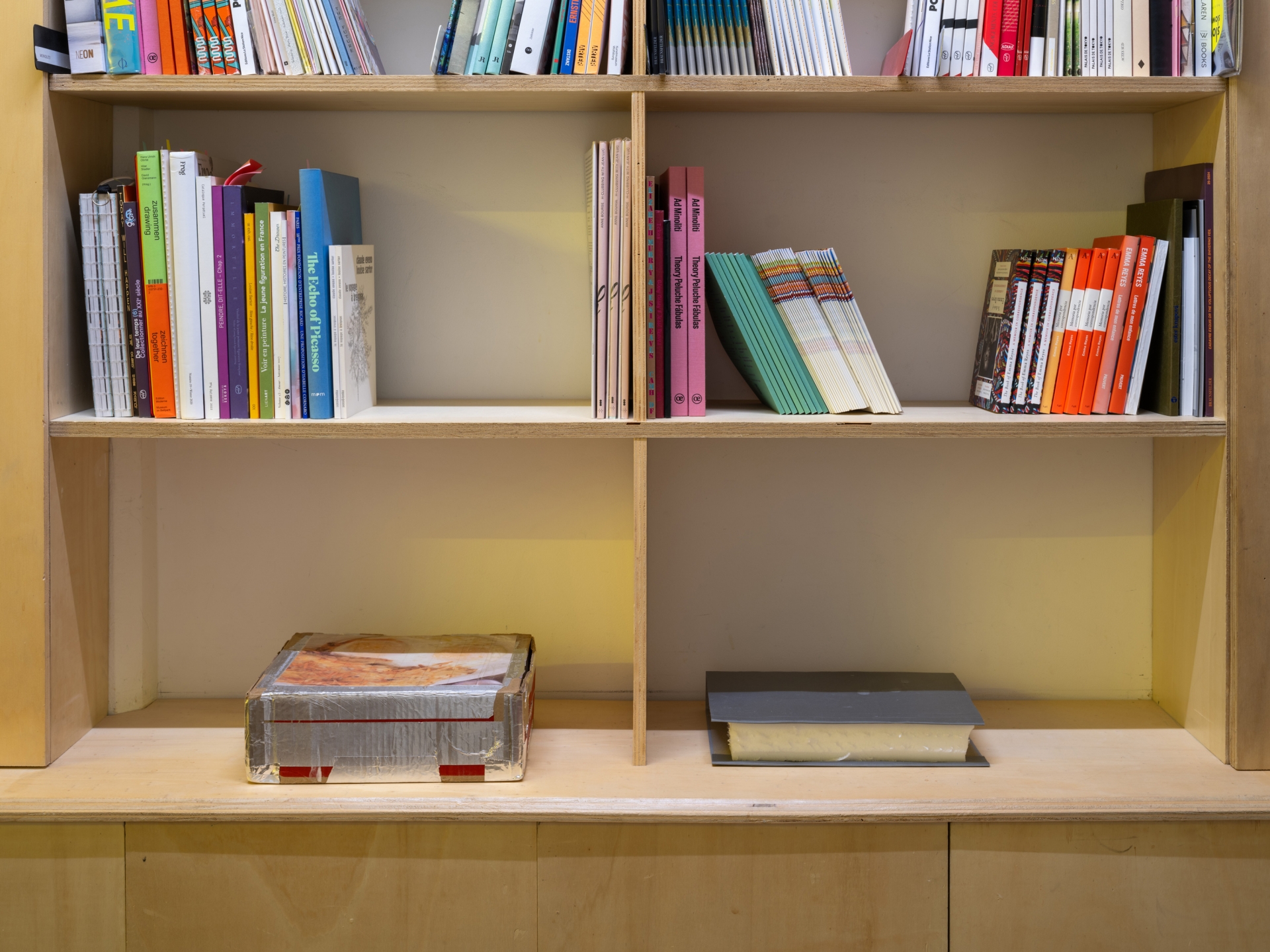

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Fleece, tv stand, 84 × 80 × 52 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Masks, led lights, 86 × 37 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Peas, 2025, Basketballs, foam, 64 × 23 × 23 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Fabric, plastic, 274 × 177 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Basketball, foam, paint, 25 × 25 × 25 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Gift, 80 × 55 × 41 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

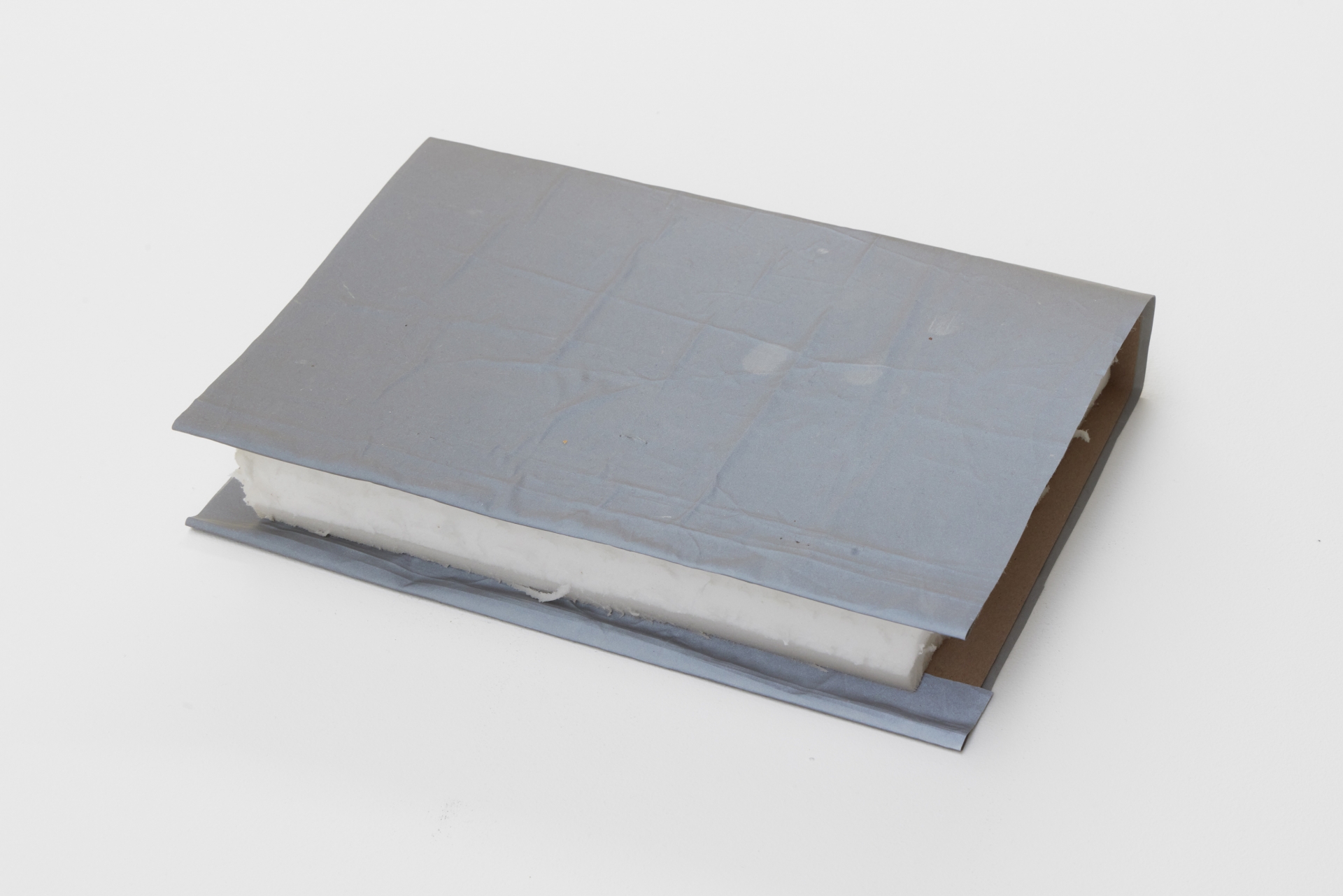

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Print, cardboard box, fossils, 31 × 24 × 11 cm

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Foam, fabric, 24 × 33 × 4 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2025, Wood, fabric, 178 × 51 × 42 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Michael E. Smith, First, 2025, Coins, wires, cow bell, electric tape, speed bag, 49 × 29 × 20 cm

Exhibition view, 2025, Crèvecœur, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris.

Work views: Alex Kostromin

Exhibition views: Martin Argyroglo

Special thanks to Modern Art

PARIS — Cascades

9 rue des Cascades

75 020 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

PARIS — Beaune

5 & 7 rue de Beaune

75 007 Paris – France

from Tue. to Fri.: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sat.: 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

and by appointment

Contact

PARIS — CASCADES: +33 (0)9 54 57 31 26

PARIS — BEAUNE: +33 (0)9 62 64 38 84

info@galeriecrevecoeur.com