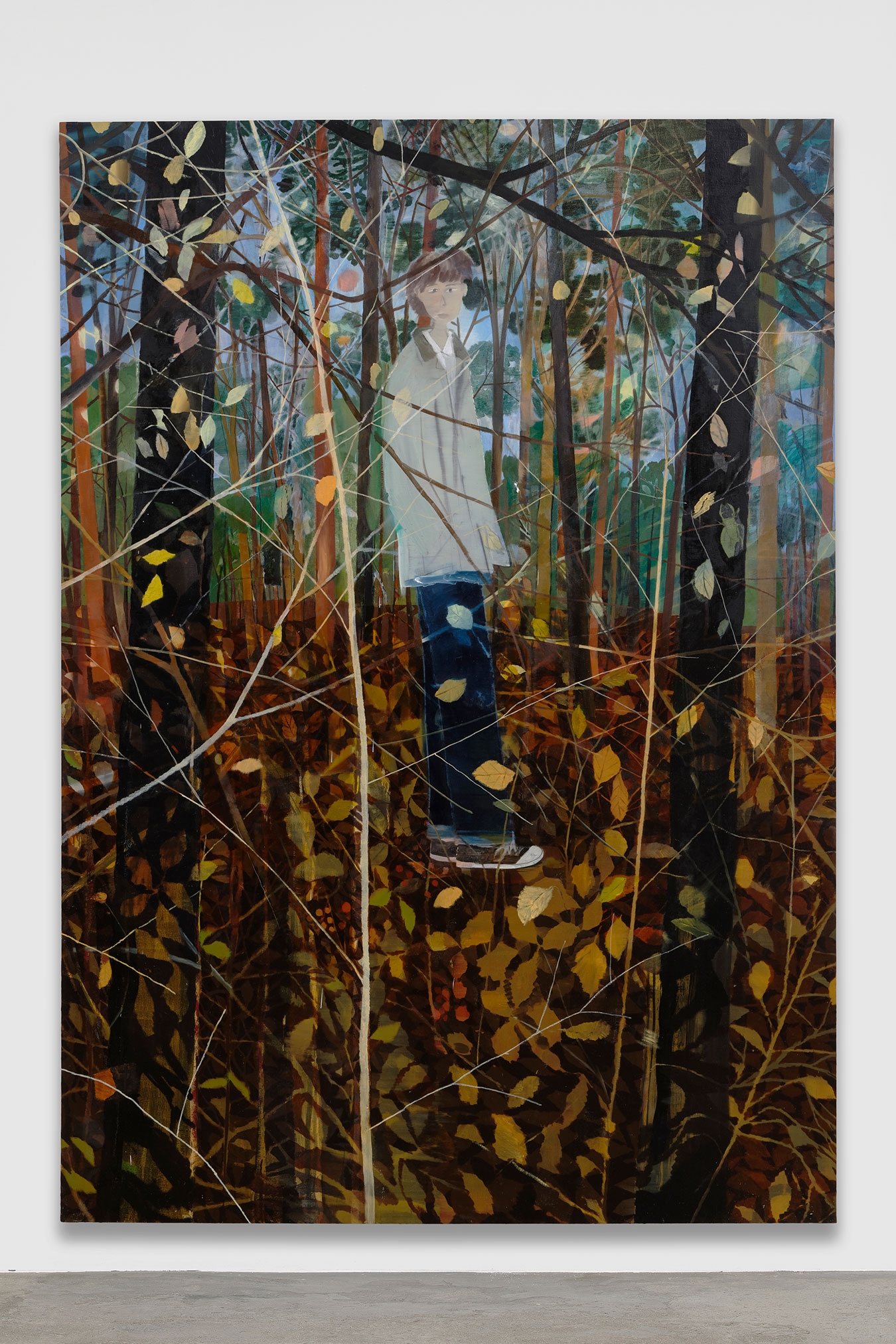

Dans la première exposition de Yu Nishimura à la galerie, qui se trouve être également sa première exposition en Europe, il y a treize peintures, toutes réalisées en 2020. La plus petite, Arts and crafts mesure 27,3 × 22 cm, et la plus grande Thicket, 259 × 182 cm. Ce qui apparaît en premier, c’est l’effet de superposition entre plusieurs couches, qui provoque un léger désalignement. Ce glissement qui s’opère dans sa peinture rend (littéralement) floues les frontières entre le réalisme (se rapportant à la mimesis photographique) et l’abstraction (l’univers inhérent à l’image), entre le premier et le dernier plan, et entre les différents points de vue avec lesquels le spectateur regarde la peinture. Alors que l’on regarde des œuvres planes, accrochées au mur, l’espace au centre n’est pas vide ; il est animé par ce qui se joue dans les peintures et entre les peintures. La zone de démarcation entre intérieur et extérieur est ici volontairement ambiguë.

Evoquant lui-même sa peinture, il écrit « It is an entrance; I cannot move forward unless a dog is more than a dog, or a cat is more than a cat. » Il serait intéressant de traduire ce terme entrance par le mot français « amorce ». Une amorce c’est le début de quelque chose, ce qui constitue la phase initiale d’une action. L’amorce c’est aussi - peut-être doit-on désormais dire « c’était » - ce morceau de film ou de bande magnétique placé au début et en fin de bobine pour en faciliter la manipulation. Et lorsque l’on interroge Nishimura sur ses influences picturales, voilà qu’il cite Takuma Nakahira, photographe et critique photographique japonais (1938-2005), auteur d’un livre radical et révolutionnaire For a language to come, qui fait se succéder sans logique et dans le flou, des paysages urbains, des fragments de rue, des passants. Il définit lui-même son style are, bure, boke (brut, flou, sans mise au point).

On se souvient que la peinture japonaise avait pour convention, au moins jusqu’au XVIIè siècle la perspective dite « en vol d’oiseau », soit en hauteur et légèrement en diagonale. C’est la technique du fukinaki yatai (littéralement « sans toit »). On peint des maisons dépourvues de toits afin de rendre visibles ce qu’il s’y passe à l’intérieur. Cela implique des compositions ambiguës entre l’intérieur et l’extérieur, entre le premier plan et l’arrière-plan. Progressivement, sous l’influence occidentale, la perspective centrale (linéaire) gagne du terrain tandis que dans la peinture occidentale le « japonisme » abolit le point de vue fixe, qui assignait au spectateur une position « de face » vis-à-vis du tableau. Et qui abolit également le second plan. Chez Nishimura, la synthèse est troublante, et il accentue ainsi l’effet d’empathie qu’on met en jeu, avec ces paysages, ces animaux, ces portraits. Car l’histoire des perspectives, il l’a aussi assimilée, comme tout individu de notre ère digitale, à l’image en mouvement. Peut-être nous met-il alors sur la piste d’une « post-image », dont on ne sait pas vraiment si elle provoque en nous une représentation, un souvenir, une apparition ou une disparition. Scene of beholder (scène de spectateur), c’est le titre de l’exposition de Yu Nishimura. C’est aussi la promesse de son récit pictural.

Loading

Loading  Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Motion, 2020, oil on canvas, 60,6 × 50 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Sunset reflected on ocean, 2020, oil on canvas, 53 × 45,5 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Pause, 2020, oil on canvas, 130 × 97 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Meandering, 2020, oil on canvas, 162 × 97 cm Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Thicket, 2020, oil on canvas, 259 × 182 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, A bird over sky, 2020, oil on canvas, 53 × 41 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

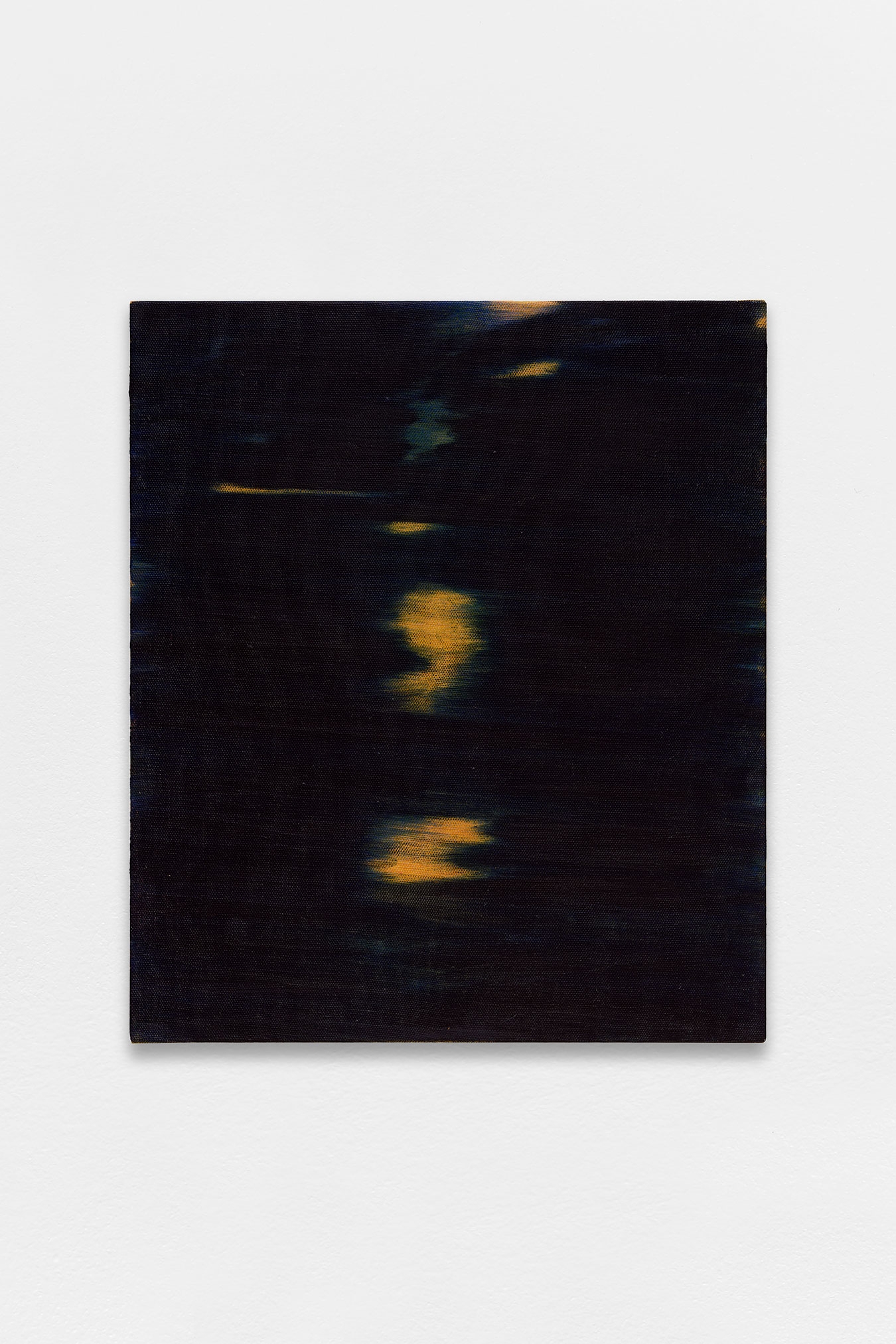

Loading Yu Nishimura, Nocturnal, 2020, oil on canvas, 80,5 × 65,5 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

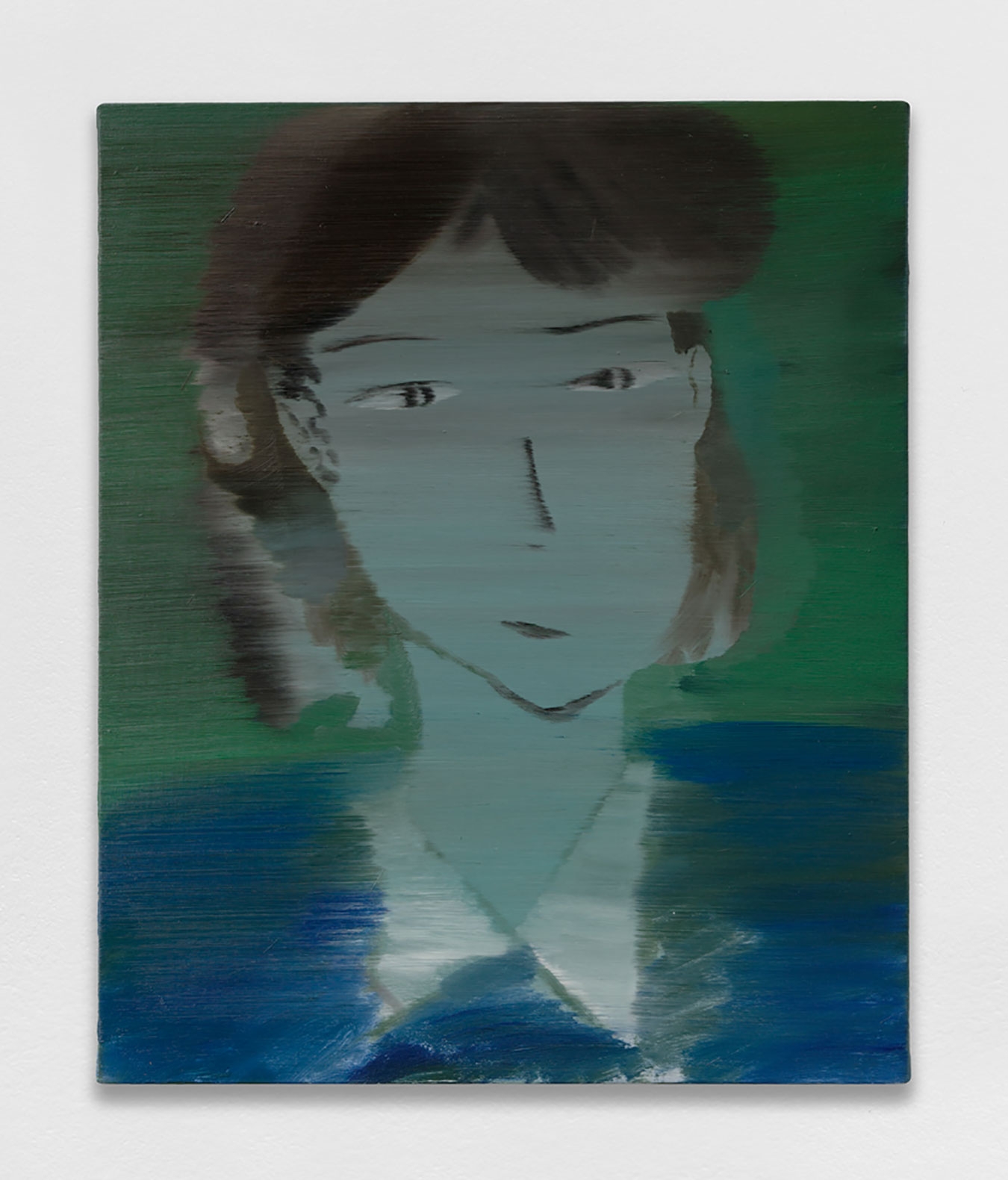

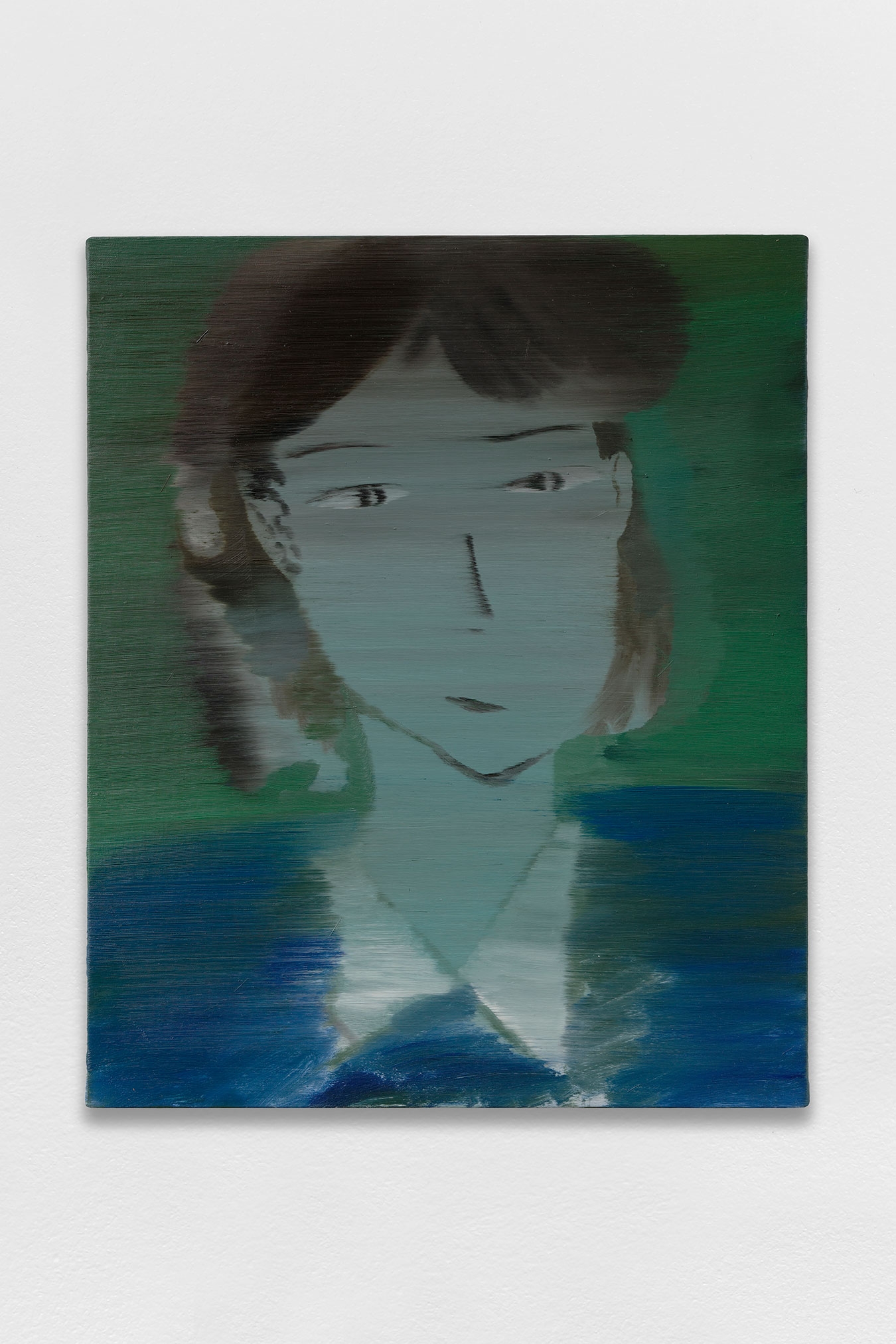

Loading Yu Nishimura, Girl in blue, 2020, oil on canvas, 60,6 × 50 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Cat on chair, 2020, oil on canvas, 65,2 × 80,3 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Arts and craft, 2020, oil on canvas, 27,3 × 22 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

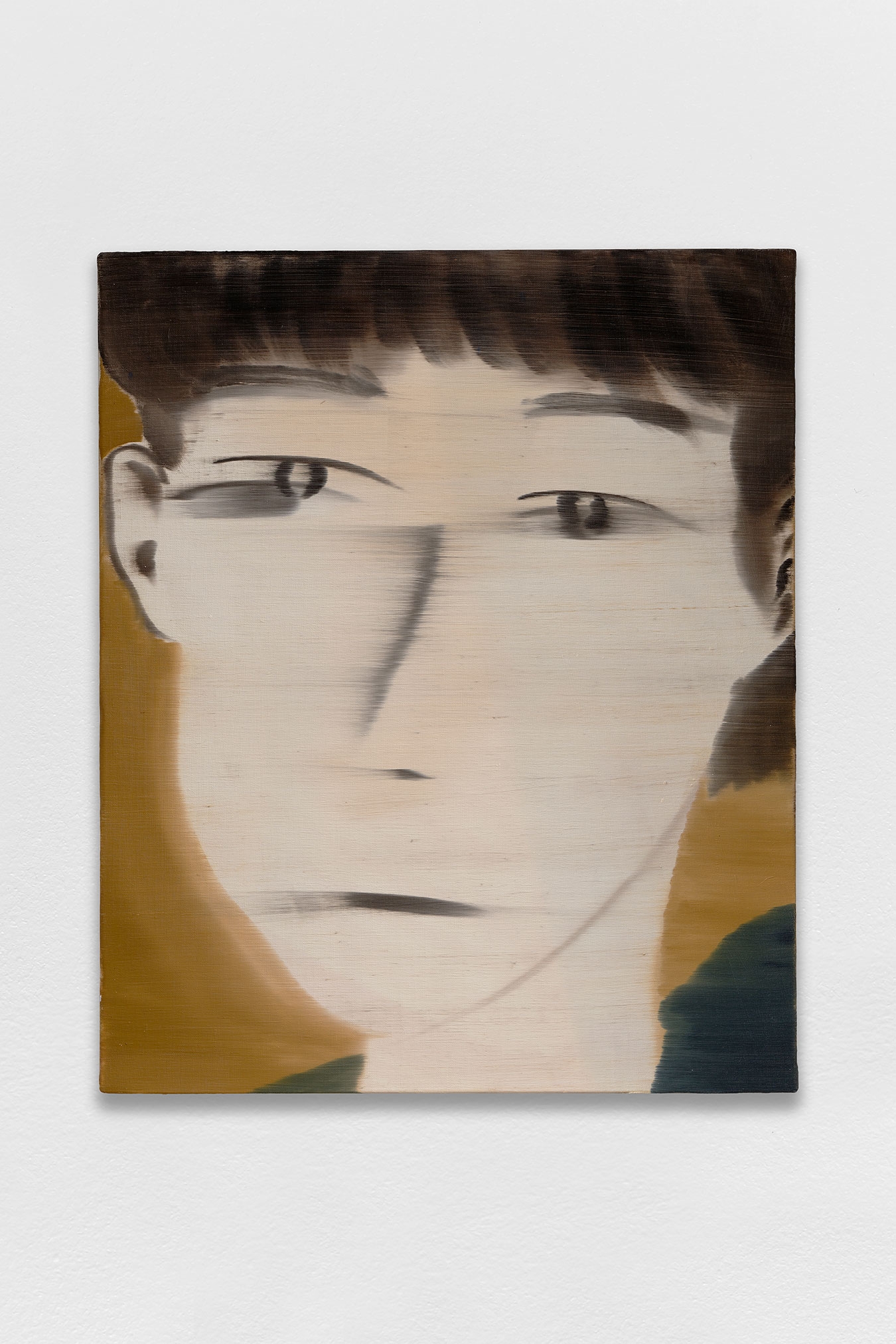

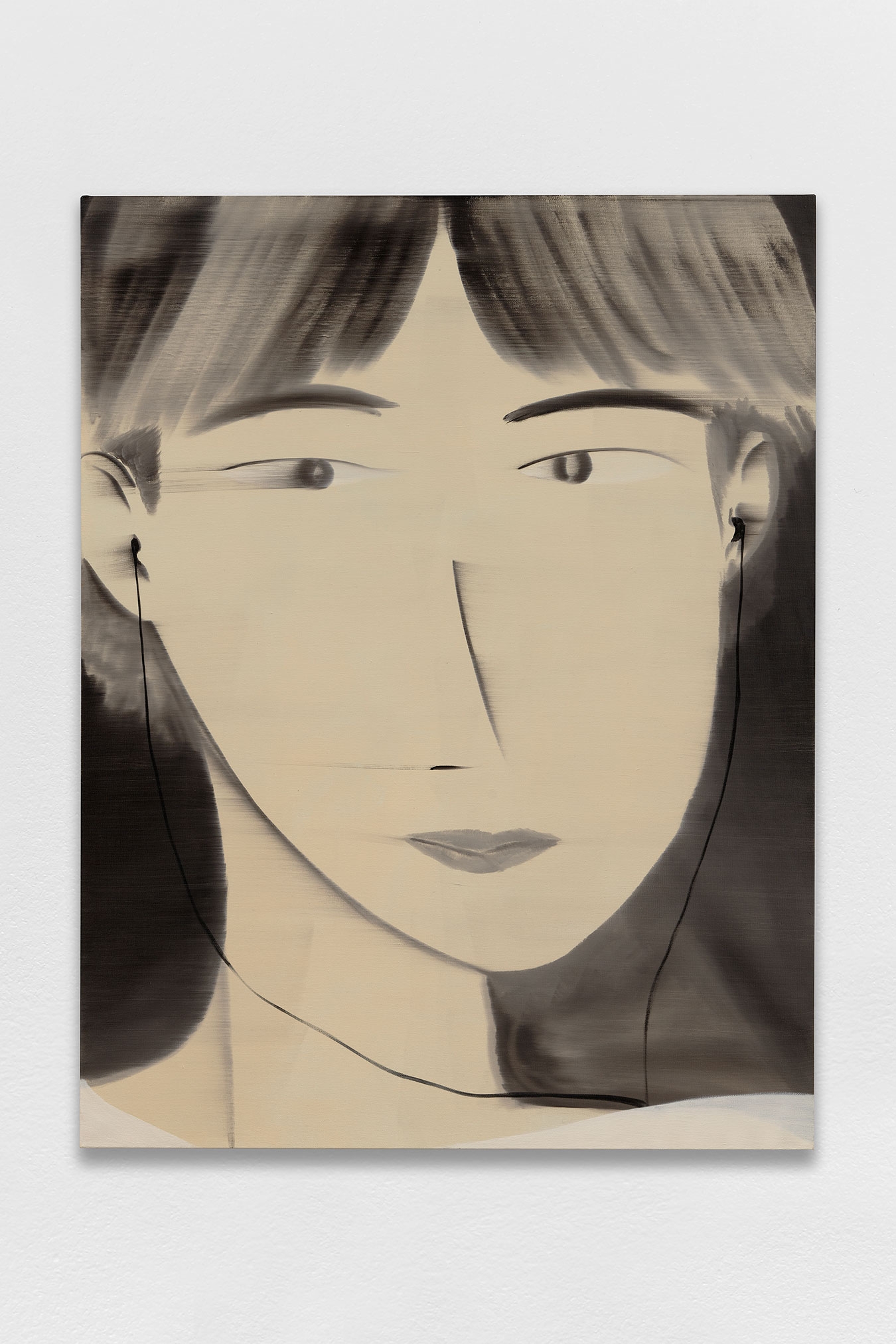

Loading Yu Nishimura, Playback, 2020, oil on canvas, 145.5 × 112 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

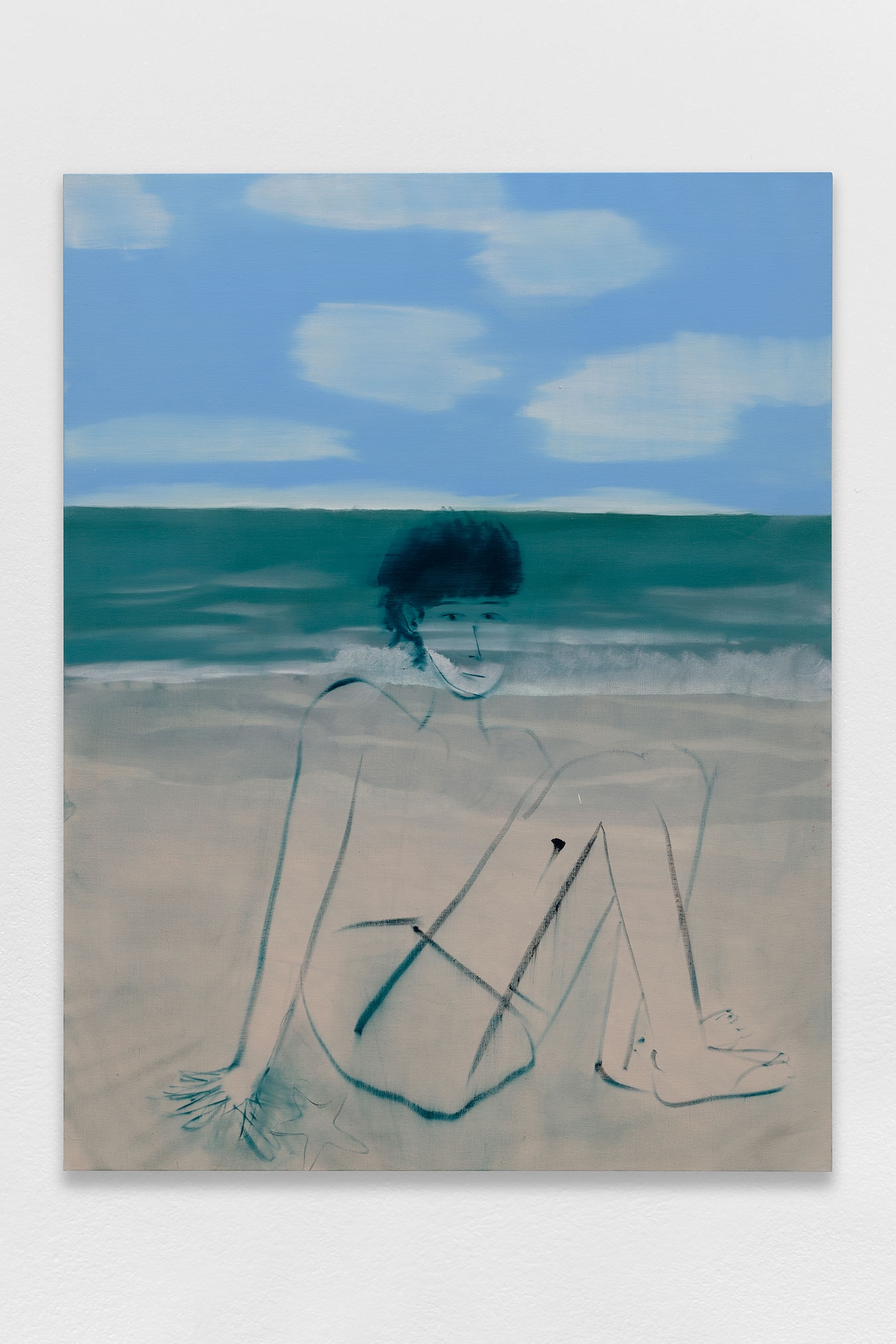

Loading Yu Nishimura, Sandy beach, 2020, oil on canvas, 145,5 × 112 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Unit, 2020, oil on canvas, 162 × 130 cm. © Aurélien Mole

Loading

Loading Yu Nishimura, Scene of beholder, exhibition view, Crèvecœur, Paris. © Aurélien Mole