« La partie langue et littérature était brève. Un seul trait mémorable : la littérature d’Uqbar était de caractère fantastique, ses épopées et ses légendes ne se rapportaient jamais à la réalité, mais aux deux régions imaginaires de Mlejnas et de Tlön… La bibliographie énumérait quatre volumes que nous n’avons pas trouvés jusqu’à présent, bien que le troisième - Silas Haslam : History of the land called Uqbar, 1874 - figure dans les catalogues de librairie de Bernard Quaritch. (1) Le premier, Lesbare und lesenswerthe Bemerkungen über das Land Ukbar in Klein-Asien, date de 1641. Il est l’oeuvre de Johannes Valentinus Andrea. Le fait est significatif; quelques années plus tard, je trouvai ce nom dans les pages inattendues de De Quincey (Writing, treizième volume) et j’appris que c’était celui d’un théologien allemand qui, au début du XVIIè sicèle, avait décrit la communauté imaginaire de la Rose-Croix - que d’autres fondèrent ensuite à l’instar de ce qu’il avait préfiguré lui-même. »

Jorge Luis Borges, « Tlon Uqbar Orbis Tertius » Fictions, 1944.

« Ce livre a son lieu de naissance dans un texte de Borges. Dans ce rire qui secoue à la lecture toutes les familiarités de la pensée - de la nôtre : de celle qui a notre âge et notre géographie -, ébranlant toutes les surfaces ordonnées et tous les plans qui assagissent pour nous le foisonnement des êtres, faisant vaciller et inquiétant pour longtemps notre pratique millénaire du Même et de l’Autre. Ce texte cite « une certaine encyclopédie chinoise » où il est écrit que « les animaux se divisent en : a) appartenant à l’Empereur, b) embaumés, c) apprivoisés, d) cochons de lait, e) sirènes, f) fabuleux, g) chiens en liberté, h) inclus dans la présente classification, i), qui s’agitent comme des fous, j) innombrables, l) dessinés avec un pinceau très fin en poils de chameau, l) et caetera, m) qui viennent de casser la cruche, n) qui de loin semblent des mouches ». Dans l’émerveillement de cette taxinomie, ce qu’on rejoint d’un bond, ce qui, à la faveur de l’apologue, nous est indiqué comme le charme exotique d’une autre pensée, c’est la limite de la nôtre : l’impossibilité de penser cela. (…) Quand nous instaurons un classement réfléchi, quand nous disons que le chat et le chien se ressemblent moins que deux lévriers, même s’ils sont l’un et l’autre apprivoisés ou embaumés, même s’ils courent tous deux comme des fous, et même s’ils viennent de casser la cruche, quel est donc le sol à partir de quoi nous pouvons l’établir en toute certitude ? Sur quelle « table », selon quel espace d’identités, de similitudes, d’analogies, avons-nous pris l’habitude de distribuer tant de choses différentes et pareilles ? Quelle est cette cohérence - dont on voit bien tout de suite qu’elle n’est ni déterminée par un enchaînement a priori et nécessaire, ni imposée par des contenus immédiatement sensibles ? Car il ne s’agit pas de lier des conséquences, mais de rapprocher et d’isoler, d’analyser, d’ajuster et d’emboîter des contenus concrets; rien de plus tâtonnant, rien de plus empirique (au moins en apparence) que l’instauration d’un ordre parmi les choses; rien qui n’exige un oeil plus ouvert, un langage plus fidèle et mieux modulé ; rien qui ne demande avec plus d’insistance qu’on se laisse porter par la prolifération des qualités et des formes. (…) L’ordre, c’est à la fois ce qui se donne dans les choses comme leur loi intérieure, le réseau secret selon lequel elles se regardent en quelque sorte les unes les autres et qui n’existent qu’à travers la grille d’un regard, d’une attention, d’un langage; et c’est seulement dans les cases blanches de ce quadrillage qu’il se manifeste en profondeur comme déjà là, attendant en silence le moment d’être énoncé. »

Michel Foucault, Les mots et les choses, 1966, préface. Le texte de Borges évoqué ici est Le langage analytique de John Wilkins, 1942.

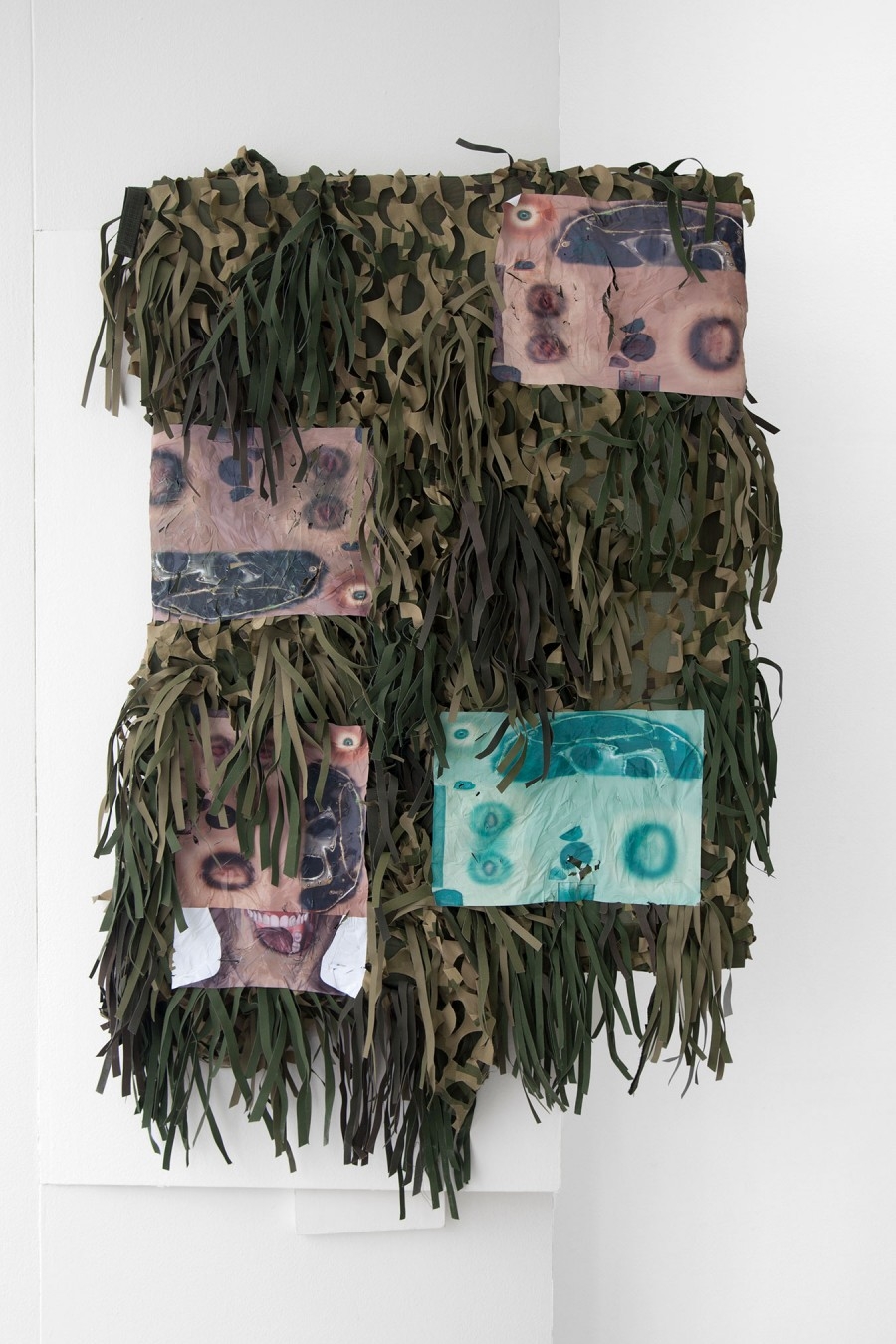

« Au début de ce siècle, une structure s’affirma progressivement , d’abord en France, puis en Russie et en Hollande. Elle est depuis lors restée, dans le domaine des arts visuels, l’emblème de l’ambition moderniste. (…) A cause de sa structure (et de son histoire) bivalente, la grille est totalement et même allègrement schizophrénique. J’ai assisté et j’ai participé à des débats où il était question de savoir si la grille induisait l’existence centrifuge ou l’existence centripète de l’oeuvre d’art. Logiquement, la grille est susceptible de s’étendre dans toutes les directions à l’infini. Toute limite lui étant imposée par une peinture ou une sculpture donnée ne peut donc être qu’arbitraire. Grâce à la grille, l’oeuvre d’art se présente comme un simple fragment, comme une petite pièce arbitrairement taillée dans un tissu infiniment plus vaste. Ainsi envisagée, la grille procède de l’oeuvre d’art vers l’extérieur et nous oblige à une reconnaissance du monde situé au-delà du cadre. Il s’agit de la lecture centrifuge. Quant à la lecture centripète, elle va, tout naturellement, des limites extérieures de l’objet esthétique vers l’intérieur. Selon cette lecture, la grille est une re-présentation de tout ce qui sépare l’oeuvre d’art du monde, de l’espace ambiant et des autres objets. Elle fait passer par introjection les limites du monde à l’intérieur ; elle projette sur lui-même l’espace contenu à l’intérieur du cadre. C’est un mode de répétition dont le sens est que l’art est une convention ».

Rosalind Krauss, « Grilles », L’originalité de l’avant-garde et autres mythes modernistes, 1986.

« Nous avons été entraînés à voir la peinture comme des « images », fictives, abstraites ou littérales, dans un espace habituellement limité et enfermé par un cadre, qui isole l’image. Il a été montré qu’il existe des possibilités autres que cette manière de « voir” la peinture. On peut dire d’une image qu’elle est « réelle » s’il ne s’agit pas d’une reproduction optique, si elle ne symbolise ou ne décrit pas ce qui appelle une image mentale. Cette image « réelle » ou « absolue » n’est confinée que par notre perception limitée. »

Robert Ryman in Wall Painting (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1979). Traduction.

- Haslam a aussi publié A general history of labyrinths. ↑